Welcome to Issue No. 13 of Prime Number:

A Journal of Distinctive Poetry & Prose

Letter from the Editors

Dear Readers,

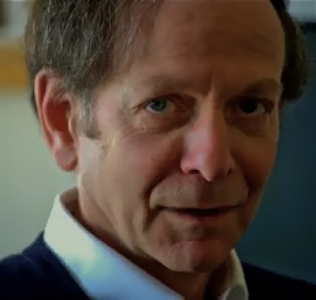

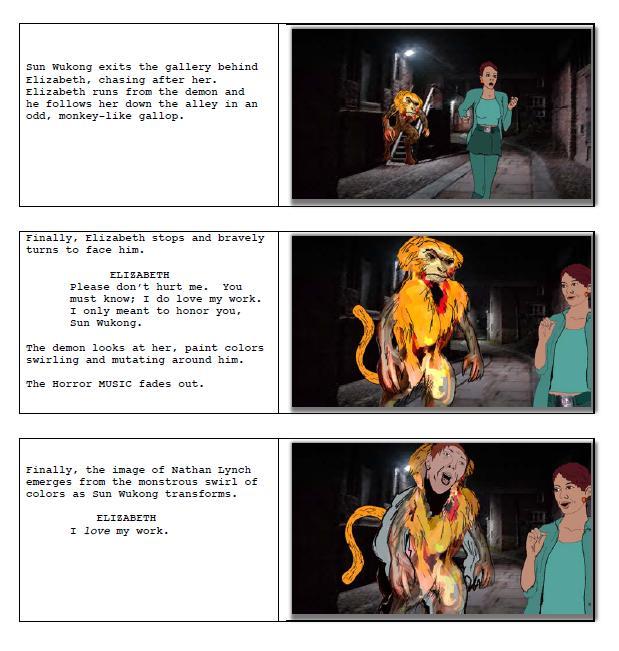

Just in time for Halloween, we are excited to present lucky Issue No. 13 of Prime Number Magazine. The only thing scary about this issue, though, is how great the work is that we're able to bring you this quarter. We've got terrific short stories for you, including work by Sybil Baker and Benjamin Buchholz, both of whom have novels coming out soon. We've also got wonderful non-fiction, including an essay by Kirk Curnutt, author of Dixie Noir, among other books. Also, be sure to check out our eclectic mix of poetry, including work by Lenore Weiss and Joe Mills. And because we think you will be doing a lot of reading in the cold months ahead (or hot months, for our friends in the Southern Hemisphere), we've got a bunch of book reviews. Lastly, we're pleased to present a story board by Emily Edwards that we think you'll love.

Our cover photo for the issue is by photographer Peg Duthie.

As we've said before, it has become increasingly difficult to turn down the wonderful work we are offered. If we have had to decline your work, please try us again! Now that we have six issues for you to look at, you should be getting a better sense of what we like.

A number of readers have asked how they might comment on the work they read in the magazine. We’ll look into adding that feature in the future. In the meantime if you are moved to comment I would encourage you to send us an email (editors@primenumbermagazine.com) and we’ll pass your thoughts along to the contributors. Similarly, if you are a publisher and would like to send us ARCs for us to consider for reviews, please contact us at the above email address. We’re especially interested in reviewing new, recent, or overlooked books from small presses.

Finally, we’ve begun reading submissions for Issue 17, scheduled to launch in January. We’d love to include your work, so please submit! We need short stories, flash fiction and non-fiction, poetry, reviews, interviews, short drama, and cover art. To learn more, visit our submissions page.

One more thing: Prime Number Magazine is published by Press 53, a terrific small press helping to keep literature alive. Please support indpendent presses and bookstores.

The Editors

Issue 13, October-December 2011

POETRY

And the Dreams of Vaudeville Follow Us All Home

Memories of Ukulele and the Girl Who Loved Her

Johnny Winter in Stockholm

Big Bill Broonzy in Amsterdam

Governor O.K. Allen Considers the Pardon Request

of Huddie William Ledbetter

Börte’s Perfect Love Story

FICTION

License to Rock

Uncle Matty Doesn't Require Collapse

The Spiritual Age of Machines

STORY BOARD

Art Critic

NONFICTION

Crosswords

The Best Cemetery in the South (in which to Kiss a Woman)

Almost Happy,1972

Living in the Zone

REVIEWS

Review of Betty Superman by Tiff Holland

Review of If You Knew Then What I Know Now by Ryan Van Meter

Review of Mending: New and Selected Stories by Sallie Bingham

Review of Fighting in the Shade by Sterling Watson

Review of Lumina by Heather Ross Miller

Poetry from Skylaar Amann

followed by Q&A

And the Dreams of Vaudeville Follow Us All Home

Step up to yesterday and yes

the heyday of play. If vaudeville

be the food of live, play on. One

more encore, encourage irreverence

and revere performer. Brava! diva,

broad, vibrato. Keep clapping till

the raven stops rapping and the only

thing knocked backed longer than drinking

is the slapsticking and the stinking jokes.

Tip tumblers, hats, and tables till wood

and glass slivers like tinder and the general

brouhaha belches hoi polloi into night

streets and sleek streetcars shift dirty men

from concert saloon to salon to one-room

studio and grave shifts worked hung over

and humming. And the ukulele strums

linger melodies in men’s heads, vibrate

lips as they slip home lately, hopes hopped

up on music, magic, and that frantic

slapstick. The chugchugchug

of the train tracks syncopate dreams

in a whole city’s brains and enflamed

aspirations for a better tomorrow haunt

the commonest man and his poor wife,

both eking out a working class subsistence.

Sitting by the radio, cheap pipe and sewing

respectively in hand, and each quietly

imagining a secret, separate,

existence: he, a professional juggler,

and she sings like a bird.

Memories of Ukulele and the Girl Who Loved Her

She was born--like they all were--on the wrong side of the tracks. Sleeping on hard bed like a fret board, listening to the woo-woo of the train wash over her like ocean waves. She saved every dream for the stage and gazed at the night stars in that certain romantic way in which the rough-and-tumbles store up hope like pinched pennies.

But the years skipped by like scratches on wax cylinders; she let her bob grow out and joined the working class, breaking back, unpacking boxes, moving up the ladder slowly--as far as a girl like her could go. Then sick and aching for forgotten yesterday, faux vaude, and joie de vivre, she heaved her zombie body from the millstone and willed her way to the great white way, a Broadway whale to her rehab Ahab.

She hit the train tracks, pulled up stakes so they couldn’t follow her. She walked away slowly awol, then running, she made her getaway. Oh, she got good, lammed it as far as her gams would get. She tapped on creaky stages, juggled in saloons, sang off key in concert halls, creeping ever closer to that Broadway Whale, with its fishtail and Mae West body that reverberates va-va-voom when you touch it.

And she touched it.

Its four-string fret board plays like a rib cage, weeps gently and shrugs off trouble. Hums melody like a tumbling wave, strums chords like a short skirt. She stopped short on the sidewalk, saw it tug her from the window. She gave the man inside the last of her juggling money, hugged the ukulele to her body. Ukulele. She said the word again, in the Hawaiian way. ‘Ukulele. It brushed her lips like kissing sublimity. She let her thumb skim down the strings and her spine shivered in the way that meant she was changed for ever. She thought back to the shack she grew up in, the pain, the factory bosses and fatcats, the humiliating auditions and rejections at one dime museum after another in every one-horse town on the small-time circuit. Never again. She plucked a few notes so sweet they brought tears to her eyes, and she knew it was true.

Skylaar Amann is a poet and artist living in Portland, OR. In 2005, Skylaar was a Kidd Tutorial fellow at the University of Oregon. Her poetry has recently been published in Cirque and Sea Stories. She writes regularly on the subjects of the sea, love, and chronic pain. When not writing, Skylaar enjoys the ocean and playing her ukulele. www.skylaaramann.com

Q&

Q: We’re on a series of one-night stands for the vaudeville troupe. What is this town we’re pulling into, where the show will set up this evening? What do you see from the train window?

A: We’re in every town in America, from New York City to Seattle and every small town in between. We’re playing in concert saloons, variety theaters, and music halls. Heck, we’ll even play a dime museum or a street corner if the price is right. Over the years, the audience ranged from rowdy drunks to high-society ladies and children. Despite the romanticized fantasy of the vaudevillian performer, life was tough…theater bosses were cutthroat and cheap, conditions were lousy, crowds were rough, hours were long, racial tensions were high. Still, I’d trade a desk job for a ukulele any day.

Q: Why the ukulele?

A: I always loved the ukulele...I just didn’t realize it until I started playing. The uke was a big part of old vaude and was ubiquitous in the films and music I grew up with everything from Cliff Edwards records to Marilyn Monroe movies). I picked up a uke of my own a few years ago, and the rest is history. While I am still learning to master the instrument, the connection was immediate...I felt a kinship with the past and an era I have always related to. The ukulele is small (perfect for my small hands), easily transportable, and above all: fun! Playing the uke, I am a performer, a jokester, a musician…a vaudevillian, which, really, since the first time I saw Harpo Marx on camera, was all I wanted to be.

Q: Are the memories and dreams of the working class spangled with sequins?

A: Growing up in a rural, low-income environment, imagination was a big part of my existence. Anything I couldn’t read in a book, I dreamed up myself. I cut my vaudeville teeth at an early age, watching Marx Brothers, W.C. Fields, and Mae West films reverently (even copying the jokes, timing, and movements in life and on paper). I yearned for the power these comics possessed...their linguistic gymnastics, anarchic

physicality, and general freedom...something not commonly found in a life of financial limitations. In adulthood, having pursued arts and academics over wealth and business (an often laborious and unrecognized task), I continue to dream of sequins...the money, the notoriety, the independence, wondering what other paths my life could have taken, and may still.

Poetry from Amorak Huey

followed by Q&A

Johnny Winter in Stockholm

Tivoli Garden, June 1984

No shadows here. You could be in Miami:

one of those places where the blues

has the bright echo of a bauble in the sun –

light plunging: white stone into rivermurk.

There’s something like home about a water city

even where the buildings are angled all wrong,

the history belongs to someone else

and the churches are unsmiling.

A long way from Leland or Beaumont

but still the sweet mildew smell of summer,

the strange blossoming of hyacinth.

When you’re seeing clearly –

no more dragons to chase – one stage

fades into next, until a high lonesome wind

bruises down from mountains

with the keening of a water oak limb

about to break free. They adore you here

but you know better – it’s the music,

not the words, your fingers telling a story

in any language, any season – it’s about love,

all the loves a man ever had

or lost, you can’t let this sunshine end

because once the song stops, baby,

you can kiss tomorrow goodbye.

Big Bill Broonzy in Amsterdam

June 1953

Some places just lay claim to you –

the way this city named for a river

where all the trees are no taller

than a man’s head has felt like home

from the hour you arrived. Summer

no warmer than March, Jim Crow’s

never set foot here – your new friends

think you’re joking when you ask

if you’ll be arrested for taking

the stage at the pub. You thought

you knew a thing or two about rivers

& women, but this girl,

she turns you inside out. She

hardly looks at your face

but never stops watching

your fingers. Her smile makes

your blood heat up, thumping

this Gibson never felt so good.

This place reminds you of a house

being built on top of the spot

where an older house burned:

all promise & possibility

& maybe even redemption.

It’s not until hours later

when she tells you her name – Pim –

& asks for a light.

Without waiting for an answer,

she leans in so close to your mouth

you smell lemons & fresh air,

she touches the tip of her cigarette

to yours, inhales

like she’s drawing electricity

from deep inside you,

in that brief glow

sparking between you

you can see everything:

the beginning, the end –

dark smeary blotches

flickering against a pale green

so bright it hurts the eye.

Governor O.K. Allen Considers the Pardon Request of Huddie William Ledbetter

July 1934

One of those Louisiana summer evenings,

peeper frogs rioting outside,

breeze just moving heat around

like the inside of an oven. Can’t tell

if it’s supposed to be funny, letter

on back of record: “Goodnight

Irene.” Fine song, but the gimmick puts you in mind

of that joke you know the newspapermen

are telling about you – dogwood leaf blows in

an open office window, and thinking

it might be a bill from Huey, you sign it.

Lord, it’s hot. Life’s too short.

You’ve been looking for something essential

you can claim as your own,

maybe this is it – think of the music,

the way a song can get inside a man’s head

and lurk there, dangerous

and erotic like blood, or water

when the river’s high against the levies,

swirling away whole Tupelo trees

from leaf to root. Hear the right

notes on a record player

and you’re twenty-six again,

back in Waxahachie

on a picnic blanket with a girl in a yellow muslin dress,

world on fire and smelling like red wine,

her mouth hungry against yours,

this was before tax assessments and highway commissions,

before this pressure behind your eyes

that you’re pretty sure will kill you someday,

before anyone owed or owned you –

when anything, by God, was possible.

Amorak Huey teaches professional and creative writing at Grand Valley State University in Michigan. His poems have appeared in Rattle, Poet Lore, Contrary, The Southern Review and other journals. More information is at www.amorakhuey.net.

Q&A:

Q: What is your favorite water city, and why?

A: It’s no secret that we humans love to live by the water. There are practical reasons for this – transportation, commerce, etc. – but there’s also something about water that speaks to us, connects with us, calms us. Raymond Carver wrote that loving rivers increases us, and that line has always resonated with me. Grand Rapids, Michigan, has a river running through it, and we’re an easy drive from Lake Michigan. So maybe this is my favorite because it’s where I live now. I am here, and there is water, and yes to both of these things.

Q: Tell us more about Big Bill Broonzy and his life and music.

A: Big Bill Broonzy was a ridiculously talented blues guitarist and singer in the first half of the twentieth century. His biography is suitably unclear for a blues legend – maybe he was born in Arkansas, maybe in Mississippi – and he worked mostly in obscurity until after World War II when he went to Europe with part of a folk-blues-roots music revival tour, where he was extremely well received and cemented his status as an icon. Also, while he was in Holland, he fell in love with a Dutch woman named Pim van Iseldt, whom he married. Broonzy died in Chicago in 1958 of throat cancer. His “Guitar Shuffle” is one of the most remarkable pieces of music ever recorded. You can listen to it here.

Q: How did you come to write these poems about music and musicians and place?

A: I wrote a poem about the legendary bluesman Robert Johnson and his alleged deal with the devil, and then I wrote another one, and then I started reading about other blues musicians and I just kept writing. I grew up in Alabama, so the songs and stories and rhythms of the South matter to me, and my father has always listened to the blues. So these poems, which make up a whole manuscript now, are about music, and place, and American history, and fathers and sons, and all these huge and important and small and personal things wrapped up in the blues. The music. It all comes back to the music.

Poetry from Joe Mills

followed by Q&A

Crucible

i.

“Tell us a story,” the children ask,

and the parents, although they know

it’s a delaying tactic, always agree.

Listen, they say, once upon a time

there were girls and boys like you,

scared and resourceful, disobedient

and loved, and there were parents,

like us, trying to keep them safe

and warm and fed, but they failed

so the children had to leave to fight

monsters and giants, witches and wolves,

and when they came back home

sometimes they found their parents

had died, but not you, you never will.

ii.

Yes, there is evil

in the world, some

directed at you

and you can do

nothing to avoid it.

Beware of strangers.

Don’t judge by appearances.

None of these will help.

Evil will do what evil does,

striking you down

even when you don’t

bite into the apple,

and if you’re lucky,

you survive, sometimes

unconscious, sometimes

in a tower (after all

there are so many ways

to be locked up)

but still alive, if not

warm, at least waiting.

iii.

You prefer beauty

to the point of wanting

someone comatose

instead of the village girl

who dances according

to her own desires

because you believe

you will be the one

to wake her, the one

to make her move,

your vivifying kiss,

your magical presence.

This is the mirror

of the tale. Stop

looking at her,

imagining the feel

of that skin, and listen.

iv

Forget they’re animals.

Forget the easy jokes

about property crimes.

Don’t stop at slogans:

“Avoid extremes” or

“Find the middle way.”

Consider only the bare

element. A woman,

a blonde stranger,

eats and sits and sleeps

in the bed you’ve shared

your most intimate moments.

Call her intruder

or mistress.

Call her daughter in law

or doubt.

Call her longing

or desire.

But she will come

and afterwards

nowhere will be

just right again.

v.

When you get home

after stealing and killing

to feed your family,

you’ll take an ax

to memory,

hacking down

the evidence

and burning

the green stalks;

the smoke will be

seen for miles

ensuring an audience

for you to recount

what happened

and what happened

becomes the tale

you tell.

vi.

Ignore the housing materials;

pay attention to the statistics.

Whatever gets built

brute force knocks down

two out of three times.

This is enough

to keep yourself fed

and something to remember

when you lock the door

before going to bed.

vii.

Blood, puberty,

sex, violence,

it may be these

sometimes, but always

the family dies.

No matter what

we do or have

in the basket,

no matter who

happens to pass by

at the last minute.

Blame the wolves,

among us, famine,

viruses, poor vision,

or tell the story

so the mother

of your mother

survives this

particular ending

but we all know

where each path ends.

Burn everything

away; this remains

the bone of the story

on which we choke.

Telling Time

A tale, like a rock,

over the years,

becomes smooth

from constant rubbing;

edges and corners abrade

until it seems no more

than a glossy ornament,

but hold it to your ear,

you can still hear

the ticking within.

Whatever gets polished

away, the violence

we do to one another

and ourselves – the cutting,

off of toes to try to fit

into a slipper, the dancing

to death in red hot shoes,

the pulling out of tongues –

this remains: the clock

will strike midnight,

the crocodile is nearing,

the last petal falls.

Hurry, each story says,

you don’t have much time.

Joe Mills teaches at the University of North Carolina School of the Arts, where he holds the endowed chair for the Susan Burress Wall Professorship for Distinguished Teaching in the Humanities. He also is the poet-in residence at Salem College.

Q&A

Q: How do fairy tales prepare children to understand their world–and their parents?

A: The crime writer Jim Thompson said that there were dozens of plots, but “there is only one story. Things are not what they seem.” Every fairy tale deals with this, and readers learn about the world’s complexities. (This, by the way, is also why I think Disney often gets the tales wrong. In Disney films, you can judge by appearances. Scar is clearly evil; he has a scar. The step-sisters are “ugly” inside and out.) Dealing with these complexities requires resilience, resourcefulness, and the recognition that there is much outside of your control. It’s good for children and for parents to understand this.

Q: What is a fairy tale that you won’t read to your children, and why?

A: I’ve kept them away from Bluebeard although I know they’ll get to him eventually. It’s less the tale than the telling that I’m careful about. Fairy tales deal with identity, so issues of race, gender, class, etc. are inevitably involved. Issues involved with adoption also come into play a great deal.

Q: If you found yourself lost in an unknown forest, what strategies would you use to save yourself/be saved/win the day?

A: Be careful who you talk to–no matter what they look like–and what you say to them. Again and again, fairy tales suggest a key strategy is to know when to keep your mouth shut. And be nice to the birds; they usually can help.

Poetry from Lenore Weiss

followed by Q&A

Börte’s Perfect Love Song*

1. Börte Sings Both Loud and Softly to Temujin

I am Mongol, loyal to one master.

When that other khan

touches my cheek, it turns into a salt pond.

Nightmares rim my eyes with darkness.

My husband, Temujin, is a gray wolf

who kissed my mouth.

I remember when Temujin lifted

the fringe of my silk banner

with his spear.

Now his spirit pole is gone from my tent.

I drip candle wax along the fissure of my heart,

drink warm kumis.

A woman in black sable calls me

to stand before my dream.

Floating seeds join each other in air.

I hear them laugh.

The seed in my bowl is not his.

It doubles me.

I will slip away like the whip of a horsetail

upon the frozen steppe.

I was not born to die in another clan's tent.

The Blue Sky follows me between branches.

The face of the marmot and falcon is Temujin's

face. The birch hides my secret.

2. The Lichen Clan

Stolen from Temujin to this mirror camp, days

stick in my throat and sicken me.

I see men, women, and children

with the same two arms and legs.

They stare

and wait for me to circle.

If I remove my silver necklace,

I must bow my neck.

How long can I nurse emptiness,

a heartless child?

The fire at night warms bootless feet.

My silver gelding with a black tail does not run toward me.

I search the Altai Mountains for rising dust.

Before a cooking fire,

I dry a blanket, the same color

as an arrow that strikes

the curved tip of a falcon's wing.

I see it.

Men come to crush each other,

and every woman and child with two arms and legs.

Stallions mash bones with hooves

into the black rock of Lake Baikal

covered with the faces of lichen

that speak as one clan.

3. Wild Onion and Pear

Lying next to this man, Chilger,

through the smoke-hole of our tent,

I hear a grasshopper

burrow in sheep dung.

He throws a hand over my chest

like a lasso pole to draw me in tight.

His breath travels up an elk-path

and comes back down, snorting.

All night, even without sleep,

I cannot rest.

I'm the one who holds his willow branch

until it topples,

and in the morning, the one who fills

a leather bucket with mare's milk

until it runs down his face

and drowns him in a white river.

I draw my lips over my teeth.

He wants to capture a smile.

He can bridle me.

No one commands my heart.

Only the child that floats on its back

with fingers pressed against my belly.

I will dig in the ground,

feed him wild onion and pear.

4. A Wolfskin with a Silk Rope

My ears hear everything at night.

My eyes see everything during day.

I could not tell who entered my tent

through the evening smoke-hole and stood

with his legs, an arrow's width apart.

Then I saw him.

Sky blue. Even his nose.

Maybe he was a cloud.

In his hand, several wolfskins tied

with a silk rope.

He said: From the water of your waters

will grow a nation. Four sons

with the strength of a wolf pack

tied together.

He placed a bundle in my lap.

When I awoke, it was my head's soft pillow.

Then I knew Temujin would come.

Who else could be the father of such men?

Part of me

wanted daughters to braid my hair,

to brew tea when news of the tangled grass

reached my ears.

Piles of rotting bodies like dead trees.

I am not prepared.

5. The Strongest Hand

Soldiers drink horse’s blood,

fill moats with dead bodies,

pile catapults with excrement

near a thousand flickering fires.

Quivers of horn and wood

hug arrows for their intended.

Ashes of men rout a birch

with locust memories.

Now I pour ashes into my palm

and blow breath on them,

men in a season of slaughter

who disappear beneath a saddle.

When I was a child,

my mother carried me on her hip.

I wore boots as soft as doeskin.

One day she found a mare,

escort to a pool of water

between shoulders of earth.

The sky grew black. I could see back

to the beginning

before I held a horse’s mane

and breathed in its sweet sweat,

where I sat and wondered why people kill each other,

and then scatter to the strongest hand.

6. A Sparrow in Search of Spring

Temujin, wolf-man with cat eyes

came to me in a goat-skin cape

to replace my companion of months,

a shadow. Now my twin flies

like a sparrow in search of spring

away to a peak covered in grass,

or like a sturgeon that leaps

with the oar of its tail.

I run free.

Night is studded with pearls

and wraps us in black velvet.

Inside each other's den,

no one sees

what we do,

our backs etched raw

by root and stone.

Thunder from our sated voices

widens a stream-bed.

Who we are together

shines in our eyes.

The child that is mine

becomes his.

Temujin has come back.

I pick out straw from his beard.

*Börte was the first wife of Temujin (Chingis Khan). She was captured by the Merkid

tribe and temporarily married to Chilger the Athlete. Chingis Khan began his drive to

unite the clans of the Asiatic steppes in an effort to reclaim her.

Lenore Weiss is an award-winning writer who lives in the Bay Area. Her collections include “Sh’ma Yis’rael" (2007) from Pudding House Publications, “Public and Other Places” (2003), and “Business Plan” (2001). Her work has most recently appeared in The Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, Nimrod International Journal, Copper Nickel, and Bridges: A Jewish Feminist Journal as well as anthologized in Not A Muse: Inner Lives of Women and Appleseeds. She is the editor of From the Well of Living Waters, an anthology of poetry.

Q&A

Q: How did you come to be interested in Börte and Temujin?

A: I attended the Genghis Khan exhibit at the Tech Museum in San Jose. As someone of Hungarian descent, I’ve always had an interest in Mongolia. The exhibit opened new doorways, including mention of the marvelous books by Jack Weatherford who traveled Mongolia for a period of five years and traced the footsteps of Genghis Khan. I was excited by a quality of language, a narrative that was based on survival and an intimate awareness of the physical world. I wanted to work toward achieving that same quality in the Börte and Temujin poems.

Q: What did you collect as a child–rocks, insects, stamps?–and why?

A: Mostly, I coveted unbroken crayons, notepaper, and books.

Q: Perhaps you would offer your thoughts on the narrative poem and its place in the contemporary poetic landscape.

A: The narrative is strong, especially in the work of young hip-hop artists throughout the world who tell stories of what it takes to survive in a difficult urban landscape.

License to Rock

by Shannon Anthony

followed by Q&A

Despite my efforts to explore fresh territory, the conversational needle—totally rejecting my venturesome metaphor—gets stuck in a gouged-out groove. See, we never meet any Eds or Eddies even close to our age, so isn't it fascinating that the name is disproportionately represented in the population of famous rock guitarists? We can never actually name that many, and that's including The Edge—how hilarious it always is to include The Edge—but afterwards there's this smiling silence like we've discovered a not-the-least-bit-boneheaded truth. This time this pisses me off.

"How the fuck would we know how many Eds are out there? What new people do we ever meet, Eddie or otherwise?"

Lisa just smiles. "I run a tight friendship."

I can't stay mad at her. I mean, I can, but it makes me a complete dick. Because she's so—I mean, she makes people feel...I mean, her home is so homey it can only be described with words I haven't learned to use properly—but I strongly suspect the presence of bolsters and sideboards and cozies.

I don't let the apartment door slam on my way out. The hallway's full of welcome mats and holiday door decor. Lisa's neighbors aren't like mine, in that none of them strikes me as likely to be interested in our services as suppliers of genuinely realistic out-of-state ID’s.

Hey, it's not about the money. We remember what it's like to be underage. So we give the kids what they need to get into rock clubs. Look, they could drink and drive themselves to death just fine without our help. The important thing to understand is that what our customers lack in legitimately issued photo ID's with late-eighties dates of birth, they more than make up for in a headbanging, hip-hopping, moshalicious, rockaholic will to make it to the next show.

Myself, I'm not getting out and about so often anymore. Good enough things can always be downloaded by those who don't care to wait. And, well, the last concert I was at, I looked around and realized it's almost getting to the point where I'm old enough to have fathered some of these kids, I mean if my genetic material at the period in question hadn't all been earmarked for Daisy Duke. You know, back in the day before anybody said back in the day.

Of course if the bands had been any good at all, I wouldn't have given a shit about the crowd, but the thing is, everybody else was seriously into the garbage. So I was like, okay, I get it. We've outgrown each other. Have fun, kids, I'm going to find new places to be young.

Because what happened to me was NOT that I felt suddenly old. I am so not old. People are always telling me how youthful I am. ("Thirty-two, huh? I'm still going to have to see some ID.")

* * *

"...and as Minnesotans, this concerns us."

Damn it, Lisa just had to go and meet herself an Edward. Dressed to impress someone who's not me, Ned is pretending he's warm enough in svelte wool. He's our age but in dress shoes taking old man baby steps to cross a piddling patch of ice. I am of course wearing traction-packed work boots. It's totally beside the point that they make me look cool. That is, the boots and the parka make me look like I don't give a shit, and that is what's cool. At least if the parka's connected to the boots by Bowie legs encased in long, lean jeans.

"Mac, you're washing these jeans every couple of weeks or so, aren't you?"

Uh huh. How would Lisa notice it's the same pair if she wasn't totally checking out my Bowie legs?

"As I was saying..." Ned is still saying. "Minnesota is a border state, and..."

And we are in a bored state. I yawn and start fishing in my parka for our most recently finished products.

Lisa gives me a warning look. "Ned's obviously very interested in the border, being Department of Homeland Security like he is.”

Wham-bam—my Bowie legs shoot out from under me, and I come down hard on an icy curb. See, being a Minnesotan means something significant is always happening to me. Mostly in the form of weather.

* * *

"It would be safer if we stop hooking...certain kinds of people up." Lisa knows what I'm trying not to say. "I don't want to get them—or us—into trouble with the Department of Ned. I mean, it's pretty serious, right?"

This isn’t the first time our feet have gotten cold. Sometimes it's looked like we won't be able to keep up with the technology, but then of course technology always puts us right back in the game. Whenever I've had doubts, Lisa's always been the one to go, "We can't quit now. It's totally the principle of the thing!"

Now all she says is: "Serious? Of course it is."

* * *

"The thing is, Lisa. I have to tell you. You should know. The truth is. Here's a fun fact." I'm kind of in love with you.

"A fun fact is where now?"

Jesus! After all the concerts we've gone to together, how the hell does Lisa's hearing not suck?

* * *

"Mac! Can we give you a lift, buddy?"

Ned is a professional threat collector. Yet he doesn't seem to feel threatened by me.

"Why the hell not?" I climb in.

But I can see Lisa wishes I hadn't. Why the hell not? All is explained when the radio informs us we are tuned in to "the best new country."

I punch Ned on the shoulder. "This is my stop! Thanks, man." I feel safe giving him the finger, knowing he can't see it.

"Mighty cute mitten you got there, Mac."

Whatever, asshole. Some of us cheerfully violate the rules of fashion if it means keeping most of the feeling in most of our extremities.

* * *

Lisa says, "I never did get my fun fact."

"Here's a fun fact: The 'best new country' is the worst music in the world."

"Seriously, Mac."

"Seriously, Lisa? EIGHTY languages are spoken in the Minneapolis Public Schools."

"Yeah?"

"Yeah. And these kids are tomorrow's professionals and parents and public servants and, yes, party animals!"

"Oh. So you're not stopping."

"I guess I can't." And by the way, your boyfriend really needs to be...well, me. "It's totally the principle of the thing."

* * *

"Mac, I'm here for the license!"

Lisa would know totally evocative words for the fabric that frames my customer's face. I don't know the cloth or the colors. What I do know is that this chick—let's call her Melody, like it says right here on her driver's license—could totally be a not too distant cousin of Iman.

I share with Melody my standard words of wisdom: "If you squander this opportunity and settle for barhopping at fucking Mall of America, I do not want to hear about it, and, frankly, you'd deserve to get busted. I mean, you just want to drink: That's what Wisconsin's for."

Young Melody assures me the license won't be wasted. That's all I need to hear, but she goes on to mention some of the establishments she'll be visiting. The names ring a few bells, and set off...twangier instruments. "Um, but aren't those places totally...?" I can't say it.

"Yes, I love—"

"You don't need to tell me! This biz is strictly don't ask, don't—"

But she tells me. She says: "Country!"

I'm not completely closed-minded, you know. I'm not opposed to the existence of Dixie Chicks, or Judds. Country music was good enough for Daisy Duke. And hell, peaceful rebellion can be such a rockin' thing, even if what's being rebelled against is, well, rock. But—country! I don't know what the world's coming to.

* * *

Here's a fun fact: Ned is Department of History.

And by the way I was totally right. That long pillow thingie that gets in the way when Lisa and I fool around on her couch? Definitely a bolster.

* * *

Kids (I now find myself saying), I totally believe that the opportunity for immediate gratification is not even close to the worst thing in the world. This license means I'm trusting you not to drink and drive. I believe in your right to culture, be it popular or unpopular. We're in the land of the this and the home of the that. And, kids, I TOTALLY believe, if your taste happens to suck, in headphones. So enjoy. We've got weather, we've got music. We're in the middle of it all, where east meets west and K stations share the air with W's. Yeah, they mostly suck, but work with me here.

Kids, understand that it IS a small world, as well as big and scary. We are Minnesotans, kids, and everything, but everything, concerns us.

Shannon Anthony lives in Minneapolis. Her short fiction has appeared or is forthcoming at Bound Off, Brink Magazine, Menda City Review, The View From Here, LITnIMAGE and Coal City Review, among other places. Her shortest fiction is tweeted @shannon_anthony.

Q&A

Q: What can you tell us about this story?

A: The first version was “finished” almost ten years ago. (Most of the intervening time was spent in denial of the need to cut a few thousand words and add a plot.) Though written in and about the wake of the September 11 attacks, this was from the beginning a very fun story.

Q: What have you been reading lately?

A: Mostly fiction. Recent favorites include Alissa Nutting's story collection Unclean Jobs for Women and Girls, Elaine Dundy's The Dud Avocado, and Ngugi wa Thiong'o's Wizard of the Crow. I've also been reading classic sci fi, and not long ago I began a leisurely journey through the works of 18th and 19th century novelists like Burney, Oliphant and Trollope.

Q: Where do you write?

A: At my dining table; at a desk that was once padded with foam rubber and used as my baby sister's diaper changing table; at a homemade standing desk (the secret ingredient is duct tape); in my head, especially while walking, washing dishes or taking a shower.

Q: Deciduous or coniferous?

A: Deciduous. (Sorry, coniferous, but what else would I say in October? Ask me again in January.)

Q: What are you working on now?

A: Thank you for asking! I'm writing a novel…but I don't like to say much about work in progress. Thank you for not asking. I also have an ever-growing list of short stories in the works.

Pan's Burden

by Stephen Williams

followed by Q&A

“My god you stink,” I said.

“I didn’t know you were so sensitive. Next time, I’ll wait for ’em to build showers before I come ashore,” my sharpshooter said.

“I smell you a mile away and it ain’t just cause we all need showers. You must have something wrong with your insides. It don’t even smell human.”

“We ain’t here to serve tea. Get back to your binoculars. I’ll let you know if I need your opinion.”

We were quiet for at least an hour before I started worrying about our position.

“Are we in the best spot?” I asked.

“I don’t know about you, but the best spot for me would be sitting on the front porch with my mother.”

“I mean here. Are we in the best spot or should we move into the valley?” He damned well knew what I meant the first time.

“We’re good right here where the Lieutenant put us. If they try to come up the valley, they’ll have to cross two hundred yards without no cover.”

With my BAR and his rifle he was right. We could have held back a whole company. Our Lieutenant warned us that fresh troops would be looking for a weak point to force their way across this island. They’d just landed, so they’d scout around.

We both shut up again and watched the valley another hour before I broke the silence again. By then the sun was half way up in the sky and it was getting as hot as a boiler-room. I saw movement at the far end of the valley. “There are some guys under that big tree, the big tree by the edge of the grass,” I said.

“Where?”

“See the top of the grassy knoll? They’re in the shade of the tallest tree. They’re just standing there looking for us. I can’t see much, but there are at least two of them.”

“I see something. It could be two heads looking our way or it could be shadows.”

“Can you take them from this distance? Do you have the shot?” I asked.

“Too much cover until they move. They know we’re here, but they’ll still try something.”

We watched and waited for some movement. They had good cover on their end of the valley and we had good cover on our end. They couldn’t go around us without crossing a lot of exposed ground and there wasn’t any place to hide if they got into the valley.

“They’re moving,” I said.

My sharpshooter slowly put down his own binoculars and pointed his rifle. Their point man stepped out from the shadows. He never saw us and my sharpshooter hit him with the first shot.

“Like the range at Lejeune.” He spoke aloud, but seemed to be talking to himself.

“What do you think they’ll try next?” I asked.

“We won’t have to wait long to find out. I doubt if they’re patient.”

“I see them two guys again. Same spot,” I said.

“They’re trying to find us.”

“Someone’s moving to the left,” I said.

“I see him,” my sharpshooter said. “Middle didn’t work out so good.”

There was a little movement behind trees and low bushes to our left. In minutes, a second man emerged.

The second man didn’t get any further than the first. My sharpshooter hit him as soon as he had a clear shot.

For another three minutes, the valley was quiet. I didn’t even see the officer poke his nose out from behind his tree.

A flock of green parrots crossed the valley diagonally. They emerged from a copse to our right and flew just a few feet above the grass height with no interest in us. They squawked so loud the whole valley froze until they passed.

“There’s another one on the right,” I said. “He’s coming up low and slow.”

Another single shot kill.

Except the rifle reports, the valley was as silent as a summer schoolyard. The taller grass swayed in the friendly breeze that cooled my sunburned neck and ruffled my blouse.

In about three minutes I saw movement again.

“Number four is at the door, coming up on the left,” I said.

The fourth man fell next to his friend. My sharpshooter dropped him at exactly the same spot as the second man.

We froze in the diamond bright glare of the sun. At this range we could stay in our little hiding hole all day. The spotters at the other end of the valley would never see us.

“Just hold tight, we’ll be all right,” I said, talking to myself more than to my sharpshooter.

Number five started up the right side of the valley. He got no further than any of the others.

“Do you think it ever snows here?” My sharpshooter asked while the report from his last shot still echoed in my ear.

“What?”

“Everything’s so green, but we’ve never seen it rain. We haven’t had a canteen full of rain the whole time we’ve been ashore. It hasn’t rained once.”

“I ain’t real concerned about the crops right now,” I said. “The corn and the cotton will be just fine.”

“Corn needs regular rain.”

“Let’s keep our focus on this valley now and check the Farmers Almanac after we finish the chores,” I said.

The sixth man followed the familiar pattern. He came toward us low and slow and on our left. Once again, my partner dropped him with one shot.

“This is getting boring,” I said.

“I wonder where they’re from. Are there any farm boys or are they all city kids?”

“I hope you ain’t starting another weather report,” I said softly. “I don’t want to hear about no corn.”

Number seven started toward us on the right. My sharpshooter let him get a few paces past his comrades. Even though he had one more bullet in the chamber, he manually removed the clip and reloaded. He didn’t want to give away our spot by having a spent clip fly out of his rifle.

A shadow darted across the face of a bush in the center of the valley. I tensed the grip on my BAR gun stock and flattened even closer to the ground. It was just a sea eagle flying in an easy arc above the valley. He drifted away without noticing us.

Number eight came toward us in another three minutes on our left. It was another single shot kill. If my shooter could see it, he could hit it.

“I think they’re trying to win the war by using up all our ammo,” he said. “Bullets cost money you know.”

“Yeah, at this rate we’ll be broke, in about eighty years. What’s their officer thinking?”

“He’s got no idea what to do,” my sharpshooter said. “He can’t go back and tell his commanding officer he failed and he can’t get past us. He might spend his whole platoon without figuring anything out.”

“He ain’t figured nothing out yet,” I said.

Number nine stepped forward on our right. He looked around the ground as if we might be hidden in the grass. He didn’t last ten seconds.

“Why don’t he just shoot them himself?” I asked. “It’d save everybody a lot of trouble.”

“Do you think human life means the same to them as it does to us?”

“I’ll be happy if we just live through this day. It don’t matter to me what they think.”

“Say anything you like; I want to know we did this thing for a purpose.”

“You think too much.”

“How can you say that? We’re not machines; we’re made to wonder about things.”

“All I’m wondering right now is whether the next guy will come up the right or the left. You should be thinking about hitting him when he does. We should both be wondering how many men they sent on this patrol.”

By then it was time for number ten on the left. He might as well have painted a target on his chest.

“What do you think it means?” He asked during our next three-minute respite. “You know, this whole thing. Why are we here; why are we doing this? What does it all mean?”

“It don’t mean nothing. We was just two guys dumb enough to enlist. Them guys down there was even dumber than us. Only they was a lot less lucky. Your kind of talk don’t do nobody no good. It’s like a kid asking, ‘why is the sky blue?’ It’s just blue, that’s all.”

“It must mean something.”

“Yeah, what are you going to do, save the world?”

“Why not?”

My sharpshooter was speaking just as number eleven emerged on the right. He took his shot and number eleven bought his fate.

“I think that was eleven, if I didn’t lose count,” my sharpshooter said. “There are two guys under that tree again. Maybe that officer is rethinking his master strategy. Maybe he’s trying to think of something else to do.”

Number twelve followed on the left. My sharpshooter dropped twelve next to ten, eight, six, four and two.

We waited the normal three minutes. Nothing happened. All we saw was tall grass swaying in the breeze.

“I don’t see nothing. There ain’t nobody under that tree that they like so much. I don’t see nothing.”

My partner watched by looking down his rifle sights while I worried the tree line with my binoculars. Fifteen minutes passed without movement.

I offered a premature opinion, “I think we got them all. Yeah, we got them all. Don’t see nothing.”

“You just keep thinking,” my sharpshooter said.

“Do you think they’ll try to come around to the north?”

“They can’t. They’d run right into headquarters company. They’d never even get through the wire. They might have already tried, now they’re looking for the soft spot.”

“I hope you’re right. I don’t see nothing moving.”

We stayed quiet for another fifteen minutes. The calm put me on edge. I was almost relieved when I saw movement from the tree line.

“Another one’s coming,” I said.

Number thirteen wore the uniform of an officer, probably an ensign. He walked toward us up the center of the valley, marching as if on a parade ground. He didn’t crouch, take cover or look around to his left or to his right. He just walked smartly up the center of the valley in plain sight and without hesitation. He drew a sword and held it in a salute position next to his stiff torso. He didn’t even pull his pistol from its holster. A single shot granted his death wish.

The sun hadn’t yet reached its apex for the day.

“This thing meant something to him,” my sharpshooter said.

“Yeah, it means we got Spam for lunch and them poor dumb slobs are lunch for the crows.”

“No, this thing means something. It must mean something and it’s my burden to find out what.”

“Forget it. You’ll go crazy.”

“If it takes the rest of my life, I’m going to figure out why this happened.”

He turned his back on the valley and tossed his rifle next to a tuft of thorny creeper grass. Then he lit a smoke from a pack I hadn’t known he had and looked at the ground for answers.

My god he stank.

Stephen Williams has a bachelor’s degree and a master’s degree from Central Michigan University. His academic concentrations were mathematics and psychology. He worked as an economist, an engineer, a financial analyst and a marketing executive. He developed residential real estate and managed a commercial vineyard.

Q&A

Q: What have you been reading lately?

A: Tomato Red by Daniel Woodrell; This Won’t Take But a Minute, Honey by Steve Almond

Q: Where do you write?

A: Any place I can find a flat surface capable of supporting a 8 ½ by 11 tablet of paper.

Q: Deciduous or coniferous?

A: Deciduous.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: I’m working on a story about a homeless man. I have not decided on a title.

Uncle Matty Doesn't Require Collapse

by Benjamin Buchholz

followed by Q&A

I’m very good at not answering questions, that’s what the mouth in the back of Adelaide’s head says as she turns away, the hair is thin there, thin and gossamer, the mouth beneath it, covered in hair, it frightens Lovely, bearded, like a backward eyeless Santa Claus, Lovely never noticed it before, why now?, the secret mouth, secret anatomy, not answering questions, dissembling as a form of flirtation,

Lovely follows Adelaide down the hallway, Adelaide turns a corner, Lovely pauses at the corner, listens for Adelaide’s footsteps to stop, they stop, the door opens, Adelaide’s door, three doors from the end, Lovely looks around the corner,

Adelaide’s hidden mouth says as the door closes on it, come have a cup of coffee with us one of these days, there are things we can share, secrets,

like the mayor?,

no, not him, goodbye now, over my dead body, I don’t share well, you see, that sort of thing, nothing personal, so I’d rather not play, that’s the easiest way to win sometimes, I’ll just sit here with the cat, we can talk about it, tell you secrets, that’s not sharing,

the door closes, Adelaide inside alone, Lovely waters the plants outside her room for a few minutes just to make sure no one has started arguing inside, no one putting on nice dresses, push-up bras, rummaging in makeup bins, what would Burgundy say about that?, premeditated, cold-blooded, disruption, wave-function collapse,

*

spooky action at a distance, isolated present, see Burgundy went to New York City once, several times, really, but only once that mattered in the entanglement, rode the subway to the end of its line, got out, looked around, walked to a café three blocks from the station, checked her watch, left a note on a napkin, I was here, where were you?, and just then Adelaide entered the café,

Adelaide!,

Burgundy!,

we'll play cards when we’re old, Parcheesi, watch the others choke on peanut shells, but golly, neighbor, we’re here now, why?, how’d it happen?, were you following me?,

it’s a random thing, it’s a mystery,

have you been to this café before?, Adelaide asks,

no, no, no, Burgundy says, she means it, and she isn’t lying,

*

double-slit experiment, passing through two women at once there must be a prediction where he ends up, wave function dictates a single outcome, a localized event, but they scatter, coherence, rage, jealousy, in a single-world theory these could be accounted, perhaps the scene twice, seen through the keyhole of Adelaide’s room, she’s got the old projector out, the wheels of tape turning, showing it on the wall, collapse, the two outcomes, the multiple outcomes choosing a single state, a solid state, at least temporarily, relative to the observer, Lovely’s kneeling in the hallway, she’s got the mop, the bucket, the observer,

*

she hasn’t been to this café before, she hasn’t written anything on a café napkin before, no reminders, no love notes, no accusations, she folds the napkin, discreetly, I was here, where were you?, dabs the corner of her mouth with it, sets it in her lap, all very open, all right in front of Adelaide, Adelaide watches the napkin,

I’m thinking about dessert, join me?,

Adelaide looks at her watch, I was supposed to meet someone but he has forgotten, I think,

that's too bad, says Burgundy, I guess it’s just you and me,

it’s a nice café at least, Adelaide looks around, she’s been here awhile, in the café, Burgundy notices, in her booth, a newspaper, folded, unfolded, newspaper ink rubbed off the pages and onto Adelaide’s thumb, bits of comic,

I was thinking about dessert too, we might as well, you can tell me how you ended up here, and alone too!, we’ll treat ourselves, we deserve it,

alone, yes, thinks Burgundy, she glances at the door as Adelaide gathers her gear, leaving the newspaper, her gear just a small purse, a hat with a band around the rim, like a flapper, how passé, Adelaide you must have been something to behold when you were sixteen and innocent, Burgundy says to herself,

they’re twenty-two, they’re rather innocent still, the innocence doesn’t reveal itself to them, of course, it never does, but they’re alone, waiting, hungry for dessert, alone in a café in New York City,

*

the reel on the old projector wobbles, the images move along the wall, over notches in brick, move as if underwater, sepia-toned, languorous, Adelaide’s sway, unchanged these 50 years, unchangeable, it’s the fish, heady with depth, meaning, certain of itself, I can swim it says, see mom, leaving home wasn’t so difficult, it’s the 50’s now, modern women doing modern things, the world isn’t innocent but it isn’t as scary as the stories you tell, I can swim in the deep end just fine, who needs the reef, crannies in the coral?, who’s afraid of that big bad shark?,

*

lovely day,

lovely,

you come alone?,

yes,

both of us, such coincidence, you waiting for someone?,

what’ll you have?, I’m thinking about the cheesecake, they say New York is the place,

maybe a flan, I’m a caramel girl,

is that the secret?, caramel?, (I’ll have to make something up,) my brother,

your brother?,

the one with the limp, I haven’t told you about him?,

(there’s no brother, of course, like innocence, there isn’t, just more abyss, less shoal, 50 years of Burgundy’s brother, he’s become epic, the lies,)

funny we’ve lived across the street from each other for almost two years now, I haven’t heard you mention him,

he’s a little bit of a family secret,

Burgundy!,

I’m ashamed, yes, I’ll be candid about it, (the lie,)

I hope it’s not too bad,

what?,

whatever he has,

it’s not contagious,

oh, thank heavens, does he visit often?,

he’s in Africa,

I thought he was meeting you here?,

he's not in Africa, (damn it,) he’s supposed to fly in, he was in Africa, Mauritania to be exact,

with a limp,

from the war,

one of those, it’s a shame,

yes, yes it is,

*

this is Adelaide’s favorite part of the film, she rewinds it, watches it again, Africa!, she’s put call-out captions above their heads, they blink in and out, their turn to shine, Lovely can see the outlines of the little stickers, their depth, they aren’t one dimensional, more like a shadow on the film itself, the edge, cartoon stickers, a thumb with newspaper ink,

*

rewinding,

lovely day,

[she’s up to something, too much coincidence]

lovely,

[until you arrived]

you come alone?,

[I told him I’d rather he picked me up at the train station, but no, he said it was too big a surprise]

yes,

[I told him I’d rather we meet somewhere more public, a first meeting, don’t know the café, I’m just glad it’s got a few other people in it, he seemed nice enough but who knows?, mother always told me to watch out for myself in New York, I’m thrilling to it, though, the chance]

both of us, such coincidence, you waiting for someone?,

[too close to the bone, maybe that’s her trick, the directness, not answering is answer enough here, and I don’t want to answer, of course I am, what do you think I just wander in on any old café three-hundred miles from Boston?]

what’ll you have?, I’m thinking about the cheesecake, they say New York is the place,

[did I even hear her?]

maybe a flan, I’m a caramel girl,

[am I being a snob?]

is that the secret?, caramel?, I’ll have to make something up, my brother,

[can she hear this?, it’s quiet in here, I’ve got to smile a little extra to keep the sound from escaping my lips, do fish like caramel?, I’ve seen the boys look at her, her husband away at work late, boys at the grocery store, construction workers down the street drilling at the manhole cover, why does she live across from me?]

your brother?,

[jealousy is a bitch]

the one with the limp, I haven’t told you about him?,

[I knew a boy with a limp once, he caught a frog when we were eleven and chased me around the schoolyard]

(there’s no brother, of course, like innocence, there isn’t, just more abyss, less shoal, 50 years of Burgundy’s brother, he’s become epic, the lies,)

[sustainable, maybe multiverse, these worlds!, I’ve got an imagination, decoherent formulation doesn’t require collapse, it’s the simplest explanation, thus Ockham’s Razor will prove it, I’m just a simple girl, really]

funny we’ve lived across the street from each other for almost two years now, I haven’t heard you mention him,

[you talk too much]

he’s a little bit of a family secret,

[like my Uncle Matty who likes to masturbate under the table at dinner]

Burgundy!,

[did I say masturbate?]

I’m ashamed, yes, I’ll be candid about it,

[I masturbate, but only when no one is around]

I hope it’s not too bad,

[it’s good, better than a man]

what?,

[we were talking about something else]

whatever he has,

[syphilis, shit, I dunno, make something up]

it’s not contagious,

[the whole world is masturbating, I want dessert]

oh, thank heavens, does he visit often?,

[in the bathtub is the best, the prickling of Epsom salt, the heat, I like having the window open, my knees sticking through suds like two islands, risen, when I climax I lift myself up in the middle like I’ve got a string from my bellybutton to heaven, lift myself up like a whole continent appearing immaculately]

he’s in Africa,

[that’s a continent]

I thought he was meeting you here?,

[he hasn’t shown up, duh, that’s why I’m alone, this is awful]

he's not in Africa, (damn it,) he’s supposed to fly in, he was in Africa, Mauritania to be exact,

[Mauritania, I know nothing about Mauritania, is it even in Africa?]

with a limp,

[that’s good]

from the war,

[whew, an end, people don’t pry about that, the ones who didn’t come home to the tickertape]

one of those, it’s a shame,

[I’m free]

yes, yes it is,

[dessert?]

*

the reel doesn’t end but Adelaide puts it away, she stores the machine under her bed, she sits on the bed, takes off her shoes, slowly she reclines, but she on her side, curled up into something like a fetal position but looser, a ball of string unwound, on her side so that both mouths may breathe.

And Lovely goes away.

Benjamin Buchholz’s fiction has appeared widely and has been featured in two editions of Dzanc Press’s Best of the Web. His first novel, One Hundred and One Nights, is forthcoming this December from Little, Brown. He writes the Middle East culture blog “Not Quite Right.” (not-quite-right.net)

Q&A

Q: What was the inspiration for this story?

A: Things jumble around. I'd been reading a little physics, Hawking's Brief History of Time. And then Saramago too, some magic realism. Seeing the elderly ladies through a keyhole that sort of combined their rivalry while separating it and then rehashing, several times over, a glossed conversation -- that's the structure of the piece. I think the structure tries to say a little something about relativity, although I didn't set out with that idea in mind. I just pictured the keyhole and everything else sprung forth from there.

Q: What have you been reading lately?

A: I'm taking a masters degree in Near East Studies at Princeton and so I'm drowning in academic reading. Its good stuff, very mind-expanding to read about medieval Islamic scholars and trace their work through various commentaries and such (which is a big portion of one of my classes) and its a nice break from the real-life world.

Q: Where do you write?

A: All over the place. A lot of it at the kitchen table, which probably accounts for various mentions of food cropping up at strange and unanticipated times.

Q: Deciduous or coniferous?

A: Deciduous. Spring and Fall my favorite. Without the deci there is no spring and no color in the autumn.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: I've got a first book of fiction called One Hundred and One Nights coming out from Little, Brown this December and am working on, almost finished with, a second one. One Hundred and One Nights is set in the small Iraqi town where I worked for a year whereas the new book delves into and fictionalizes some experiences I had while traveling the middle east this last year.

Petite Suite Printanière

by Robert Wexelblatt

followed by Q&A

1. Ouverture en Ut Majeur pour Chœur Aviaire, Sonnette, Pivert, et les Jonquilles

Bessemer lolled in his La-Z-Boy drinking a cup of Earl Grey. Before his retirement he wouldn’t have touched the stuff. Iced tea in summer was fine, but only old ladies and Englishmen drank hot tea. He pictured the Earl as effete, snobbish, bewigged. Bessemer disliked that he liked that hint of bergamot and wasn’t grateful to his cousin Ida for sending him a selection of Twinings (how do you pronounce it?) for Christmas. But then he’d caught the first of the three colds he’d had that winter and found the tea made him feel better. Now he’d come to prefer it to coffee. The tea was at least more useful than the necktie Fred and Marcia sent him from Florida. “Be a snowbird,” said a card featuring tinsel on a palm tree. “Come on down.” The tie was turquoise with white gulls all over it. The last time he’d worn a tie was at Bill Burrell’s funeral; you didn’t wear a turquoise tie at a funeral, let alone one with seagulls all over it.

Bessemer glanced at the old man fishing on the cover of the L. L. Bean catalogue. For guys like that retirement is good. Not for him. For him it didn’t mean canoe trips with well-behaved grandsons; it meant tea-drinking and boredom. There’s no proper routine, nobody to shoot the shit with; you watch too much TV and start looking forward to shows as if they were visits with friends; you take afternoon naps and wake up checking for symptoms; you hardly care what you eat but put a lot of pepper on it. You drink hot tea.

The winter had been ferocious and interminable. He had hardly left the house but still he managed to come down with three colds. Where he lived March was called mud-time and for good reason. But this year the snow didn’t begin to retreat until the month was over. Now it was April and the Gormans’ daffodils were up. Bessemer imagined that, had he married, his wife would have planted bulbs so that when she left him or died he’d have daffodils every spring to remind him of her. Florida? It’s hot and flat, one big waiting room, hangs down like an old man’s organ.

Small as it was, his house had cost him more to heat than he expected. Not only was oil sky-high and the winter brutal but he was home all the time now, usually in an old fisherman’s sweater and a fleece on top of that. Twice the Jeep had needed a jump. The shoveling was risky; the sky usually gray; the prospect, in every sense, dreary.

When the doorbell buzzed he nearly spilled his Earl Grey. He hadn’t heard an engine, no car crunching up the gravel driveway; the Gormans never stopped by. The buzzing was odd, too—five short blips, as if the button were just being tapped rather than pushed.

He went to the door, stretched to look out the window at the top. Branches with a fuzz of pale green, empty sky. He opened the door cautiously.

The front yard was filled with birds, like in that old movie. There were sparrows, both brown and gray, junkos and chickadees, a pair of cardinals, four blue jays, a gang of grackles. The big bird on his step he recognized as a flicker. Black mustache and bib, barred feathers, gray skullcap, red blaze. There used to be a flicker came round but he hadn’t seen it for years. Maybe this was the same bird.

The flicker bounced once, examined him up and down with its yellow eye. “There used to be a feeder,” it said.

“What?”

“Round the back. A feeder. For seeds.”

The host of birds set up a row. The flicker swiveled his head around toward them, then back to Bessemer. “I don’t particularly care for seeds myself, of course. Worms, ants, insects—seeds only on need. But these—” he swiveled again, the bright slash of red drawing Bessemer’s admiration, “these do.”

“Then why don’t they speak for themselves?” said Bessemer, feeling more amused than crotchety.

“Don’t be ridiculous,” said the flicker. “They can’t talk.”

Bessemer didn’t bother to ask why the flicker could. What he said was, “I see.”

“So . . ,” drawled the flicker, “they’d appreciate it if you’d maybe fix up a feeder, keep it stocked—sunflower seeds, please, for the jays—and, well, that’s about it.”

Bessemer considered. “Why didn’t you ask last Fall? It would have made more sense.”

“I was in Georgia. Look, it was a hard winter for these guys. They don’t migrate. Some of them even froze. You understand?”

“I suppose so. They don’t need a feeder now but they want me to get in the habit. For next year. That it?”

“Exactly!” The flicker hopped in a circle. The seed-eaters fluttered and set up a cheer, or so it seemed to Bessemer.

That afternoon he cranked up the Jeep and drove to Home Depot to get lumber and nails for a bird house, then to the garden store where he bought a trio of squirrel-proof feeders, finally to Costco, where he picked up two twenty-pound sacks of mixed millet and cracked corn. He was about to leave when he remembered to grab a ten-pound bag of sunflower seeds.

Over the next week the flicker alighted from time to time in Bessemer’s yard, snapped up a few grubs, checked out his work, and, apparently satisfied, flew off.

2. Le Hosta Énorme, Concertino Aigre-Doux en Vert et Jaune pour Piccolo, Flûte, et Absence

Home Despot her friend Julie quipped. It opened in March and by the middle of April Johansens’ Nursery announced it would be closing. Ginny knew the Johansens; she liked them and their store. She expected they would be resentful and make one of those angry Big Box speeches. In fact, they were almost giddy with relief.

“We’re not getting any younger.”

“Got a good price for the land. Better than we’d expected.”

“We’re moving to North Carolina—up in the hills, you know. Fine climate. Temperate.”

“Lots of ex-military.”

They were having a clearance sale. Ginny bought a pair of secateurs, flats of tomatoes and pansies. The perennials were mostly gone (perennial’s my favorite horticultural word, said Julie); but back in a corner, up against the chain link fence, half hidden by a fallen shelf, Ginny spotted an outsized green planter sprouting attractive bluish-green leaves striped with yellow. The hosta looked strong. There was no little plastic tag describing the plant, no watering directions or Latin name. Mrs. Johansen said she wasn’t sure what sort of hosta it was and called her husband over. He scratched his head, perhaps distracted by thoughts of hanging out with retired master sergeants and fighter pilots, and said vaguely, “Big one, I think. Dig down about at least a foot. Give her plenty of room; that’s the ticket.”

When she picked Jeremy up from school she told him she’d been to the garden store. When they got home she took him into the back yard to show off the new plants. She wanted him involved.

“What do you think? Row of pansies here?”

“Put the tomatoes by the fence,” he said like a son of the soil. “Dad said that’s best.”

“What about this?” She pointed at the hosta.

“What is it?”

“Hosta. Broad leaves. It’s a perennial.”

“A perennial?”

“That means it comes back next year. You know those things around the big maple in front of the Belfiglios’? They’re hostas.”

“Oh,” he seemed disappointed. “But this looks a lot bigger and it’s not all green.”

“I’d like you to take care of it. It’s yours.”

“What do you mean? It’s not like it needs to be taken for a walk, Mom.” Jeremy never missed a chance to remind her of the dog she wouldn’t buy.

“Don’t be fresh. I mean you get to choose where to put it. You dig the hole, you water and feed it. It’s supposed to be a pretty large one. Have to dig deep and give it lots of room.”

“How big will it get?”

“I don’t know. Maybe a couple of feet? We’ll give it regular shots of this.” She held up the box of plant food. “See? You screw this hopper thingee to the hose and just spray it on every couple of weeks. The water mixes with the powder. Pretty cool, eh?”

Jeremy shrugged. He was doing that a lot. But he went to the garage and came back with the spade.

“Change your clothes first.”

Stan was on his third deployment. He was supposed to be home in September, unless they declared another stop-loss or something worse happened. E-mails weren’t so frequent this time around, Skype conversations even less so. Ginny knew that meant he was in a rough place. Jeremy wasn’t taking it well; for that matter, neither was she. Jeremy sulked. Stan had missed his eighth birthday, their anniversary, Christmas, New Year’s, Groundhog Day. When the car broke down and needed a new what’s-it, money was a little tight for a while. Ginny caught herself looking at men in a way she didn’t like.

Jeremy insisted on pasting a map of Afghanistan on his bedroom wall. He’d sent away for it, paid for it with some of the birthday money from her parents. Ginny no longer put on the evening news and tried to distract him from updates about the war. It was useless.

Jeremy chose a spot a good four feet from the fence and dug deep. She gave him a handful of superphosphate and showed him how to mix it in. He shoveled some of the loose dirt back then filled the hole with water. “The roots will be able to spread out easily, get a good start. Right?”

He checked the plant every day, marked the biweekly feedings on the calendar, patted handfuls of red mulch around its base. The hosta took hold and began to grow; it grew fast. Enormous leaves opened out all the way to the fence, new ones sprouted above them, then more and more. By June it took up nearly a third of the yard and was taller than Jeremy. He invited friends home after school to admire the prodigy. “Check out how thick the leaves are,” he told them.

“It’s humungous,” they admitted. “Awesome,” they said. Ginny could see the children weren’t really interested in the gigantic hosta; they only wanted to please Jeremy. They feel sorry for him, she thought sadly. But then, so did she.

The last day of school was a feeding day and Jeremy rushed home to set up the hose. It was warm. Ginny poured two glasses of lemonade and took them out to the patio.

“It’s still growing, Mom,” Jeremy shouted across the yard, pointing to the top of the plant. It was nearly as high as the spruce tree. Maybe it wasn’t a hosta after all. Hostas aren’t tall.

Jeremy dropped the hose and came over to get a drink. “It’s like the beanstalk,” he said proudly. “You know. Jack’s.”

“Well, you’ve taken very good care of it,” said Ginny.

“I really have.” His face was already in the glass. He gulped and mumbled something.

“Huh?”

“I call it Dad.”

“What?”

He came up sucking air. “Daddy.”

“You do?”

He nodded. “Because it’s tall and I love it. And because it’s a perennial and you said perennials always come back.”

3. Cadenza Pour Alto Solo, Généralement en Troisième Vitesse

Where am I going, you ask? You want to know where I’m going?

Weeks ago, years ago, in some other life, in what I thought was real life, in May, in expectation, in distress, in spite of, in the face of, in an excess of confidence, in downright panic, I pedaled toward the sun, turned my back on a whole seaboard, my job, boyfriend, mother, sister, Honda Civic, cousins, needy niece, my boss, hairdresser, retirement plan, laptop, bagels, new black dress, Facebook, Nana’s pearls, Jane Eyre, my ex-boyfriend, married ex-lover, favorite bistro, Thai takeout, shoe store—weeks ago, years ago, I left for a Sunday afternoon ride, my customary route, the standard twenty-one miles, started pedaling west on Route 20 but didn’t turn on Weston and then didn’t turn off on Sudbury either and haven’t turned yet or needed to because I had my MasterCard and L. L. Bean Visa and Amex in my fanny pack and it costs hardly anything to keep going and not only is my health holding up despite rainstorms, wind, hamburgers and motels, but I feel powerful, lithe, a hard-bodied sylph; but, as you ask, it’s my belief that there’s still a long road ahead because, you see, where I’m going is as far as I can go.

4. Quator à Cordes avec des Fauteuils Roulants, en les Trois Movements, Assez Brusque, et Un Interlude, Pas Trop Longue

“April morning in the park. Not dark.”

“A lark!”

“Nary an aardvark, loads of bark.”

“. . . Think that guy might be a nark?”

“Enough, my dear. I’m just not, you know, up to the mark.”

She guffawed. “Oh, you!”

It was one of their games of old. To her its source was lost in prehistoric mists; to him, the day before yesterday.

They both knew she came as often as she could so she never offered excuses and he never reproached. She had a big job running corporate relations for the Museum, and the hours weren’t exactly regular. He mused sometimes—not often, what was the point?—how it would be if she married, had children, if he’d had more of them, if his wife had gone on living for more than ten days after she was born.

Dad’s no complainer, she thought proudly. Not once since the accident, not an instant of self-pity. Wheelchair now, maybe an operation later. How did he fill his days? Well, he was drawing more. Last week he’d asked her to bring a soft eraser, a pad of number 80 textured paper, three pencils. He still went into the office on Tuesday mornings. He called one of those special cabs.

*

That it was so blatantly ironic only made it more cruel. She’d been a ballerina, had played tennis better than her husband, the athletic health-nut whose heart gave out so inconsiderately. Four times club champion. She had danced Odette, Juliet. Now her right hip was shot, like her husband’s heart, likewise her left knee, and she couldn’t stop being sore as hell about it.

“Hate this damned thing.” She struck the sides of the wheelchair.

“I know, Mother.”

“No. You don’t.”

He stopped at a bench and aimed her away from himself so she faced the meadow.

“After the physical therapy,” he said. “Then we’ll see.”

She looked around at him. “Why aren’t you mad at her?”

He sighed. “Because she was brave. Because she did what I didn’t have the nerve to do. I’m relieved. I’m grateful.”

“I never liked her.”

“I know that. So did she.”

*

-They might meet. They could pair off. Why not? For what other reason are they in the park? Age-appropriate. Seasonal. They all fall in love with each other. A double-wedding in June.

-Give me a break. That’s worse than improbable; it’s sentimental.

-Is it? They’re all damaged. So many wounds looking for balm.

-Exactly. One of them could pull out a pistol and shoot the others.

-You don’t like happy endings?

-I like superheroes and Ossian’s verse and the last inaugural address.

-You just don’t believe in them; is that it?

-Correct. These four people are in the park. It’s springtime. They’re all unmarried for various reasons; all lonely, incomplete, and crippled. The father and daughter are crazy about each other; the mother and son evidently aren’t. You want to be Jane Austen?

-I’d love to be Jane Austen.

-And you think she was happy?

-When she was writing, yes.

- Lizzie’s wit and D’Arcy’s cash. It’s an irresponsible satisfaction. It’s girlish.

-My, you’re pompous today. In dreams begin responsibilities.

-So they say. But not in fantasies. Fantasies are willed evasions.

-So, where exactly does a dream end and fantasy begin? He’s taken with the way she walks. She likes the sound of his voice. She remembers flirting with him at a dinner party long ago. He’d like to draw her portrait. He asks her to get a cup of coffee. Come on. It’s spring. Loosen up.

-While were quoting: April is the cruelest month. Remember?

-Sure, and February’s the longest. In fact, you’re still in it—or it’s still in you.

-. . . No wonder I love you.

-What’d you say?

-I said I love you.

-What? You do?

*