Welcome to Issue No. 43 of Prime Number Magazine

A Journal of Distinctive Poetry & Prose

Letter from the Editors (or jump to the Table of Contents)

Dear Readers,

It's time for another issue! And we think it's a good one.

To see work from previous issues, check out the Archives, or order Editors' Selections Volumes 1 and 2, shipping now from Press 53. And keep an eye out for Volume 3, which is in preparation.

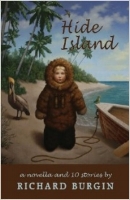

In this issue, we continue to bring you distinctive poetry and prose: short stories about academic civil wars and insurance claims adjusters; poems about film buffs and secret rooms; essays about boxers and bears; an interview with Richard Burgin, author of sixteen books including his latest, Hidden Island; and reviews of three novels. Our fiery cover photo is by Pierre Houser.

We are currently reading submissions for Issue 43 updates, Issue 47, and beyond. Please visit our Submit page and send us your distinctive poetry and prose. We’re looking for flash fiction and nonfiction up to 750 words, stories and essays up to 5,000 words, poems, book reviews, craft essays, short drama, ideas for interviews, and cover art that reflects the number of a particular issue. If we’ve had to decline your submission, please forgive us and try again!

A number of readers have asked how they might comment on the work they read in the magazine. We’ll look into adding that feature in the future. In the meantime if you are moved to comment I would encourage you to send us an email (editors@primenumbermagazine.com) and we’ll pass your thoughts along to the contributors. Similarly, if you are a publisher and would like to send us ARCs for us to consider for reviews, please contact us at the above email address. We’re especially interested in reviewing new, recent, or overlooked books from small presses.

One more thing: Prime Number Magazine is published by Press 53, a terrific small press helping to keep literature alive. Please support independent presses and bookstores.

The Editors

Issue 43, October-December 2013

POETRY

To My Husband on the One-Month Anniversary of Our Separation

Hard to Believe

Conversation at Tastee-Freeze: Stage Five

Tama-no-ura, camellia japonica

Jitsu-getsu-sei (the sun, the moon, and the stars) camellia japonica var. 'Higo'

Punica granatum 'Wonderful'

FICTION

Personal Earthquakes

The Claim Narratives

This Hallowed Ground

NONFICTION

The Boxer's Story

Under Control

Bearanoia

BOOK REVIEWS

Review of David Jauss's Glossolalia

Review of Pamela Erens's The Virgins

Review of Richard Burgin's Hidden Island

2 Poems by Dana Curtis

Followed by Q&A

For My Demons

Obsessively collecting boxes because we’ll move

again eventually no matter what

we may have collected

or what harvest is nearly complete. So much

was left to rot, left behind –

and now, I’m answering the door

in a black lace skirt and there he is – so pale

with his long slender fingers and eyes

only linguists might comprehend. Afterward,

mice surrounded the bed.

I said “sit” and they sat.

“Roll over” and they rolled over.

“Play dead” and they were very convincing.

These revolutionaries are very obedient. Afterward,

they chew through the wires, die for the cause.

When he knocks at my door again, we stare,

aghast, at the ornate brass knocker – we inhabit

this rippling world with a hollow tooth and an endless

lunatic glass pouring riot into the street – synecdoche

spells my name and he has

a box full of angry mice,

brand new and on sale.

Four Addictions for the Film Buff

(director of photography)

Wait in the place of no

understanding, the vision of thunder

like the last meal, like memory’s

grasp: in the long-ago, I was

what could be called

not quite a ghost, more

a rumor lost in editing, exhalation.

(star)

He looked in the mirror and could

not walk away. We prefer to remember

him in his finest role:

his self without soul, without

craft. Voice shadow: oh what

do we have here? Close-up. Fade out.

(Screenwriter)

It was really her creation – every

word, each setting but she was

melancholy in a bottle of wine, walking

through a black field bleached with

white stones. When she said: “disappear,”

there was an emptiness that withstood

penetration more perfectly than she had

hoped. She says no.

(Director)

The director has left the set, this

location was never intended. She curls

up in the gazebo. She watches

the River and her disappointment

follows her to a gravity

well and she falls. Every knife

becomes her fingers asleep

in the false red light. Our

starvation.

Dana Curtis’s second full-length collection of poetry, Camera Stellata, is now available from CW Books. Her first full-length collection, The Body’s Response to Famine, won the Pavement Saw Press Transcontinental Poetry Prize. She has also published seven chapbooks: Book of Disease (in the magazine, The Chapbook), Antiviolet ( Pudding House Press), Pyromythology (Finishing Line Press), Twilight Dogs (Pudding House Press), Incubus/Succubus (West Town Press), Dissolve (Sarasota Poetry Theatre Press), and Swingset Enthralled (Talent House Press). She has received grants from the Minnesota State Arts Board and the McKnight Foundation. She is the Editor-in-Chief of Elixir Press and lives in Denver.

Q&A

Q: “A rumor lost in editing” from “Four Addictions” – poets know that revision is necessary to pare the work down to its essence, but what is lost as well as gained in the process? Have you edited a poem out of existence?

A: Unfortunately, I have edited poems to death. It’s a fine line between necessary editing and unnecessary surgery. I have never learned, with absolute certainty, how to tell the difference. I like to believe I’m getting better at it. As the poet, it can be almost impossible to truly stand outside a poem and see what’s really there, what it needs and what it does not. A poem is a living thing; it should be treated as such. If you chop off the limbs, you might not be able to put them back again. If you fail to remove the unnecessary aspects, the whole poem can be dragged down. Caution is recommended. Do what has to be done without killing the patient.

Q: Might you share with us some of your favorite films, and why?

A: This is a dangerous question. You really don’t want me to get started – I can go on and on. Regardless, the best film I’ve seen in the last few years is The Dead Girl. He shows what can be accomplished with a nontraditional narrative. Many movies choose to concentrate on the murderer. In The Dead Girl, everything revolves around the dead girl. It’s one stunning piece of filmmaking. I loved David Lynch’s Inland Empire. I am also a big fan of the director, Luis Buñuel. I recently saw Buñuel’s unfinished film, Simon of the Desert which led me to some very interesting and enjoyable research on St. Simeon Stylites. I eventually wrote four poems, one of which is eight pages long, because of that movie. I also love old movies: The Thin Man, Sullivan’s Travels, The Big Sleep, To Have and Have Not, Casablanca,… There are so many. I love independent films and documentaries. As I said, I can go on and on.

Q: What do you hear on first waking at your house?

A: I hear the birds outside my window, I hear the buses in the street, I hear my dog whining to be let out, I hear my own thoughts scrabbling around the room.

3 Poems by B.A. Goodjohn

Followed by Q&A

o My Husband on the One-Month Anniversary of Our Separation

In the absence of children, we placed checks against animals:

four cats and hens to remain with me; the dog moved

to your side of the page along with the sectional sofa,

the king-sized missionary bed, the Smith Mountain watercolors.

While you moved out, bought new sheets, acquired

a phone number I need not learn, installed another

electric perimeter fence around four acres of real estate

I will never visit, I pet-sat my own dog;

at night she paced, chewed my baseball caps to damp spirals,

went cold turkey. Day found her insanely panicked, at peace finally

in the back of our old car, her long blonde nose resting

on the Jeep’s rough carpeting, one ear unflopped and cocked.

Last week, while you pet-sat the cats and hens, I visited my parents

to explain our separation, a situation I thought as fragile as the eggs

the Rhode Island Red had been brooding for a fortnight.

And today you drove eight miles to the airport to pick me up,

and I’m with the dog in the back of the car, her tail beating

a soft tattoo, snout burrowed beneath my leg. A strange land,

this back seat–watching your fingers upon the steering wheel,

your tanned arms, the shirt I have laundered for seven years–

and I wonder at the choices we make: at the dog’s, to hunt

down comfort in cars; at mine, to tell my mother you are stupid

but essentially a good man; at yours, to bring your girlfriend,

to open the car door for her, to give her my front seat.

Hard to Believe

(after Suzanne Gardinier’s “Impossible”)

Was that your breath trapped inside my answering machine

late last night? Still calling. Still speechless. Incredible.

This freesia swaddled in a green sheath. A bud fat pact.

A shifting to shame the loup-garou. Incredible.

Glassed incarceration of our separate cars at Main

and Tenth. Both inmate and visitor. Incredible.

Maggots dance a mole through diamonds scattered on the lawn

—the wing shadow of a thousand crystal starlings. Incredible.

Both your flawed daughters, decked in spring glitter and candied

heels. Smiling. Polite. Our dying eggs. Incredible.

Barbara T. Tom M. Benny B. Judith L. Big Jeff.

Wayne C. Shane B. Vicky D. All dead. Incredible.

My mother, content, planning her last sofa, last stove.

I, content, plan the excision of my womb. Incredible.

That given the round of graves, cremations, burials

at sea, we plant gardens, pregnancies. Incredible.

Beginner, begin with life. Don’t forget your mother,

your meds, bees. Be quiet under critique. Incredible.

Masked and gowned, crooking your day-old granddaughter, tracing

her knuckles with your finger. No, your finger print. Incredible.

Dear Breath, Here are the keys to her lungs. Come and go

as you please. No expectations. Yours, Incredible.

Conversation at Tastee-Freeze: Stage Five

We had other days, their moments

amber-locked—the lawn beyond the museum;

the swings in Miller park; your front room

with its stacked maze of magazines and mail,

cigarette smoke a mezzanine above

the baby grand—all loud with your prophecy:

how my husband would leave; how I would know

when to put the drinking down, where I might go,

who I might find there to help me.

How there are things we cannot predict:

how one day, you would call me beautiful

and I would hear you; how in three years

a beauty spot on the side of your mouth

would signal a movement, a silent protest

of rogue cells, threading like mycelium

across your breasts, into the hollows

beneath your arms to shoal like piranha

in the eddies of your brain, to feed

on everything you had left to tell me.

On the drive to UVA, we drowned

in a dearth of words, your head beating time

on the window. And in the consulting room,

packed with little-boy oncologists

in white coats, too starched, too clean

for this prognosis, your anger ricocheted

off their rookie concern. Random

phrases—Door Jamb! Bean Pole!

Cock Sucker!—snagged in the broken

nets of your memory.

What need had they for stethoscopes today?

Then silence ‘til Amherst when you tap

the steering wheel, say, Snow Queen.

We park facing the freeway, open our windows

so the wind and speeding cars might rock us.

Ice-cream smeared chocolate across your chin,

your hair wild and wind-knotted, you grab

my face between your sticky palms,

say, It’s okay, say, It’s the end

of the world, say, Goodbye, say,

Tsunami. Say, Beautiful, Baby.

B.A. Goodjohn is the author of the novel Sticklebacks and Snow Globes. Her poetry and fiction have appeared in a variety of publications including The Texas Review, Cortland Review, and Connecticut Review. In 2011, she won the Edwin Markham poetry prize. She teaches English at Randolph College in Virginia and blogs at www.bagoodjohn.blogspot.com

Q&A

Q: You write that “one day, you would call me beautiful/and I would hear you.” Why is it easier for us to accept criticism than praise?

A: I wish I knew. The solving of that secret could have saved me from many therapists’ couches. I’ve never been good at handling compliments. Perhaps it is because there is a part of me that feels somehow fraudulent. When Judith told me I was beautiful that day, she meant I was beautiful inside. At the time, I was unable to accept that. I was days away from heading into a rehab, and I felt far from beautiful. Or perhaps it is because I sense that a compliment somehow brings with it a responsibility: if I accept that I am beautiful/wise/clever/talented—whatever—in this moment, I will have to go on being that thing in the future. And that’s too heavy a burden for me.

Q: What do you hear on first waking at your house?

A: Claws. My cats and the dog wake early and begin to move around the house in search of goodness knows what. I can hear their claws clip and clatter on the hardwood floors. All journeys include a layover at my bedside. It’s as if they are checking to see if my eyes are still closed. Sometimes I feign sleep and they head off again, clicking from room to room. My punishment then is to wake to my iPad. The alarm is a terrible song I downloaded for free in Starbucks, and I am sick of it.

Q: When she says “Snow Queen,” all the richness of that Hans Christian Andersen story was evoked. The Queen kisses her hostage child “only twice: once to numb him from the cold, and the second time to cause him to forget.” Was this story in mind when you wrote – or perhaps you have other thoughts to share on that shattering last stanza.

A: Yes, absolutely. That terrible day and all those that followed struck me numb for many months. It was only on sharing memories of that day at her funeral that I defrosted everything about our friendship and moved towards this poem. I’m blessed that I was kissed only once.

2 Poems by Claudia Serea

Followed by Q&A

The secret room where all the creatures go

Come with me,

I’ll show you a secret room

with furniture borrowed from trees.

Arthritic hands are knotted into chairs.

Knuckles twist

into headboards and tables,

and a piece of bark holds the mirror.

The winds blows

through empty eye sockets

and whistles through the tiny holes

in flute bones.

Don’t be scared.

In the back of the room,

the old milliner lady sits on a stump

and fashions felt hats

with ears and horns.

She sews fleece and skin

and leather.

Behind her, on wooden pegs,

squirrels, rabbits, and chipmunks

beg to be set free.

You can sit

and watch her needle in

and out of

the shiny button eyes.

Her hands are quick.

In this room no one speaks,

not a peep,

or squeak,

or an open beak.

Dust falls

on the furniture of time.

She says,

You’re next, dear,

and makes me a hat

of grass roots

and sunrise.

When it rains in Rutherford

Skinny as sticks,

two shadows share

one breath.

He’s an old heron

that won’t die

even though spring has awakened

seeds in his belly

that eat

and grow when it rains.

She’s a mute nightingale

too scared to talk,

to think the thoughts.

It rains in Rutherford for days,

for weeks.

They cling

to every moment,

the way water clings to the leaves

and tears

to the throat.

By clinging,

they prove they’re alive.

In the small, white house

on Maple Street,

two birds listen

to the rain on the roof.

It rains in Rutherford,

and they can hear

angels walking in the backyard,

barefoot.

Claudia Serea is a Romanian-born poet who immigrated to the U.S. in 1995. Her poems and translations have appeared in New Letters, 5 a.m., Meridian, Word Riot, Apple Valley Review, and many others. A two-time Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net nominee, she is the author of Angels & Beasts (Phoenicia Publishing, Canada, 2012), The System (Cold Hub Press, New Zealand, 2012), and To Part Is to Die a Little (Cervena Barva Press, forthcoming). She co-translated The Vanishing Point That Whistles, an Anthology of Contemporary Romanian Poetry (Talisman Publishing, 2011) and translated from the Romanian Adina Dabija’s Beautybeast (Northshore Press, 2012). Read more at cserea.tumblr.com.

Q&A

Q: You are both poet and translator – how do you approach the words of a poet working in another language, and what can be gained as well as lost in the translation?

A: I approach every translation with a mental rolling of the sleeves. When translating a poem, the satisfaction is similar to what you feel when building something with your hands, a useful object, something that works. There are difficulties, of course. Some of the musicality and the sounds of the original language might be lost, hopefully replaced with new sounds and a new musicality. Rhyme and meter are always hard to reproduce. But, in my view, the gain is far greater than the loss. The translated poem opens a door to a new landscape and takes the reader on a trip to, say, Romania. How fun is that?

Q: You offer a surprising image of “angels walking in the backyard, barefoot.” We think of angels as lifted by wings, not earthbound. What else can you tell us about the nature of your angels?

A: When my daughter was very young, she taught me that angels (and monsters) are real, and not necessarily connected to religion. They walk among us, disguised as people, even as animals. That’s how my book Angels & Beasts was born. The angels eat, sleep, love, and make mistakes. Their wings are merely accessories they can take off and put back on as they please. I continue to write about angels, and they don’t mind showing up in my poems. They are cool like that.

Q: What do you hear on first waking at your house?

A: Birds, lots of birds in my backyard trees. Then, the alarm goes off, always too early.

3 Poems by Daniel Nathan Terry

Followed by Q&A

Tama-no-ura

camellia japonica

for Natalia Belén Guadarrama Nicosia (August 29, 2009)

In English its name is the hidden jewel. Found

in 1947 by a poor woodsman in a forest near Nagasaki,

not so far from where the bomb fell

and not so long after, it is the only wild japonica

that is red, edged in white. Adding to its beauty,

its growth is vigorous, though its habit is weeping.

To see it, imagine a flower of red fire giving off white smoke.

Or a duster of cerise feathers edged in chalk,

meant only for small hands. Imagine a cloisonné cup

of red enamel and mother of pearl—something given

by someone believed to be lost, something precious,

if only to you, now returned. Imagine a beautiful bell

of silence.

Jitsu-getsu-sei (the sun, the moon, and the stars)

camellia japonica var. ‘Higo’

Favored by Samurai who believed

as much in the cultivation of beauty

as in the art of war,

the Higo has never caught on in America.

The center of its flower is a sunburst

of hundreds of golden stamens, perfectly formed.

But the single petals are small and misshapen.

Rather than shun the flowers for their flaw,

the Samurai saw the distorted petals as a reinforcement

of the perfection in the flower’s heart.

Hundreds of years before I planted Jitsu-getsu-sei

in my garden, they wrote poems to its ancestors,

and planted rootings of these Higos

by the graves of friends and lovers.

It is one of the few camellias that drops its aging flowers

cleanly from the branch onto the earth,

each fallen blossom a spirit’s face looking back

at its body, but without any unsightly clinging

to what is already lost.

Punica granatum ‘Wonderful’

In freak cold snaps, gusts of arctic air

brown the white japonicas, ruining them

like fine white linen used thoughtlessly

to wipe up a spill of tea. On those days,

even the southern gardener must look to the dormant

plants that promise, rather than display, beauty.

Look at the pomegranate tree—naked,

leafless—a bouquet of long gray twigs fanning

up from the mulch. Look closer. See

those pale green nubs every few inches

swelling from the smooth bark? Look inside

them, and believe—in a way you would never allow

yourself when it comes to your own promise—

that come Spring, a fringe of green leaves will grace

these limbs, and then more than a hundred

flame-orange flowers, as if there is no end.

And come Fall, when the japonica buds are swelling

with new blooms, this pomegranate will be heavy

with fruit that the first cold night will split, offering

their deep sweetness to your hands like casks

filled with garnets, their flesh to your lips like a wineskin.

Daniel Nathan Terry is the author of four books of poetry: City of Starlings (forthcoming from Sibling Rivalry Press, 2015); Waxwings (Lethe Press, 2012); Capturing the Dead (NFSPS Press, 2008), which won The 2007 Stevens Prize; and a chapbook, Days of Dark Miracles (Seven Kitchens Press, 2011), which was a finalist for the Robin Becker Prize. His work has appeared, or is forthcoming, in many journals, including Cimarron Review, The Greensboro Review, and New South. He lives in Wilmington, NC, with his husband, artist Benjamin Billingsley. Daniel is currently completing two novels: The Guardian (a YA Queer version of the myth of Eden) and Never Go (a Southern Gothic set in a plantation very like Drayton Hall in South Carolina, near the town Daniel was raised in).

Q&A

Q: Japan has gifted Carolina gardens with lovely camellias, as you’ve written. What native plant is your favorite, and why?

A: And I have about 80 camellia cultivars in our garden here. Native plant? There are so very many that I love and look for. I suppose if I had to choose, it would have to be the Live Oak. I think of them as a higher life–they are certainly longer lived than any human, and I mean by many centuries. The ones at Drayton Hall (where my new novel, Never Go, is set) are my favorites. They struck me mute the first time I encountered them. They also feature prominently in my poetry–in fact, in my third full-length collection of poetry, City of Starlings (forthcoming from the wonderful Sibling Rivalry Press), they are in so many of the poems. I think it’s their age, what they’ve been witness to, the way they reach out rather than up, as if they love the earth more than the sky. I love them. True story–when we moved from Greensboro to the Cape Fear River basin and looked for a house, Benjamin gave the realtor two requirements for our new home: it had to be under $80,000, and it had to have an extra room that he could use as his painting and printmaking studio. My two requirements? The lot the house was on needed enough room for a camellia “forest,” and it had to have a Live Oak that was at least 100 years old. The realtor thought I was kidding, He said no one buys a house because of a tree. He soon found out that he was mistaken. And so we share our lives with a grand Live Oak at the foot of our garden.

Q: What do you hear on first waking at your house?

A: The dogs. They are still on my old landscaping schedule, and they like to get rolling by 5 a.m. My husband and I don’t mind, as we like to get to work on our art (he is a wonderful painter and printmaker) before the hood wakes. Over the summer, as I was dealing with my second of what will be three spinal fusions, I barely slept due to the pain. Then, I rose before the house and went into the garden in the pre-dawn to get some peace through beauty. It was like clockwork, the songs of others from 2 a.m. until after sunrise: first the Whippoorwill, then the Mockingbirds, then the rooster down the road, then the Cardinals, the Robins, the Wrens, and the Cicadas. Wonderful cacophony of need and desire. I miss it now that fall’s come.

Q: The pomegranate as the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge – what argues for that fruit in place of the apple?

A: Well, Val, I think you know I was a working horticulturist for many years, until I had to give it up, due to a lumbar spinal fusion, nine years ago. You may not know that I was also raised by a Missionary Baptist minister and his wife, my mother who is, like her mother before her a bit of a pagan-Christian. Also, my first novel, The Guardian, (as yet un-submitted, but only in need of a bit of rewriting to get it out there, which I am doing now) dealt with that. The novel is a re-imagined, gay version of the story of the First Family in The Garden, Eve’s heroic actions to defy God for the good of man, and Cain and Abel’s (who is gay and is the object of unrequited love from his Guardian Angel, Ashurel) war. So, I do have a take on the “fruit of the Tree of Knowledge.” I think it was meant to be the pomegranate. Think about how complex, hidden, difficult it is to truly understand and accept the knowledge of good and evil. The pomegranate could not be a more beautiful and difficult fruit: Its juice is like blood-wine. Its flesh is a maze of capsules and seeds. You have to work to eat it, to gain its sweetness and nutrition. And the flowers are as red-orange and bright as a fire is. I think the confusion, the reason so many argue for the apple, is really just the influence of Greek and Roman mythology upon Biblical mythology, but it is also a simple error in language–people confuse the botanical name for apple (Malus) with the word for evil or bad–Malice (or in Latin Malum). This confusion stems from the belief that Eve’s Fall from Grace was a bad thing for man. I don’t see it that way. What good is innocence and ignorance? How do either do or give anything worthwhile to our species?

Personal Earthquakes by Henry Presente

Followed by Q&A

Dear Mr. Stevenson,

I hereby resign as Volunteer Player Transporter for the Earl Stevenson Tennis Classic (ESTC). I realize that there are still three rounds left in the tournament and that my resignation may leave you in the proverbial “lurch,” but since the police have detained me upon your request, I presume you have made other arrangements to convey players to the tennis grounds.

My actions may have cost the world two of the premier talents ever to wield tennis rackets, so yes, I admit that this criminal investigation is merited. However, sir, you have responded reprehensibly to this situation and even if I were a free man, I could not continue to work for someone of your character on an unpaid basis. In my cell, alone with my copies of Tennis World, I sometimes pause to wonder how we could have worked together in the first place.

Then I think back on our interview an eternity of two weeks ago, as the ESTC was still twinkling in the future and not smeared upon the present, and I remember that you are not a bad man, Mr. Stevenson. As I showed you my driver’s license and driving record, you showed me that I was not alone in the world. When you shared your zeal for tennis legend Karlo Kassandri’s unprecedented return to the game at age 43—and his even more improbable success—my family tree grew another limb.

Neither of us could contain our excitement at Karlo’s imminent return to the ESTC, though we were not his fans. Mere fans. Simple fans who adore his laserbeam of a serve and scalpel of a forehand. How many countless tennis stars are equally apt surgeons, dissecting their opponents on the green, grassy operating table in a few short hours? It was not what Karlo removed from his opponents’ bodies and souls, it was what he transplanted into ours: hope, dignity, and gunfire.

Could anyone dispute that when Karlo pulled the trigger during those fateful Olympic Games, we all bled? Not a pedestrian red blood, but a blood as noble and blue as the sky. There he was, standing behind the podium at his press conference, accusing the scoundrels who had demanded that he throw his match. Names dropped from his lips like lead. When the truth of the coarse words he forced through his innocent throat became too heavy, Karlo spoke one more sentence before taking a pistol from his pocket.

Do you remember those words, Mr. Stevenson?

“No jugaré este juego,” he said and then fired a bullet into his own hand, leaving a hole the size of a bleeding walnut.

Perhaps you had to wait for the translation. Until the panic had subsided and Karlo’s body could be whisked away for repair while his spirit grew gangrenous. Until the television reporters could decipher his earthy Basque accent. I do not think you speak Spanish, though his words were simple: “I will not play this game.” But for me, then a humble boy growing up in the sprawl of Las Vegas, the significance shook the soil I stood upon and I felt the tremors of a personal earthquake.

For you see, in that neon city, corruption is not so much what makes the world go round as why the world is round in the first place. It is far easier to cut corners on a sphere than a cube—the work is already done. And here was Karlo, a man who would sacrifice his livelihood in tribute to the world’s amputated corners. Who would offer his own hand as prosthesis.

There is a saying for what those scoundrels, those sporting officials and so-called friends, each asked Karlo to do by lying down on his match: they asked him “to play ball.” But Karlo didn’t want “to play ball,” he only wanted to play tennis.

“No jugaré este juego,” Karlo said and fired the gun into his hand. The blood dripping down my television screen seemed to pool upon the carpet in my family’s living room. Alone, I watched the puddle grow.

My father was at the bar wagering on soccer matches he would never see. He did not keep up with the players or teams, just the fixes. His winnings were complemented by steady checks from an accounting glitch that a friend in the government had arranged. My mother was busy at her department store job, relieving her cash register of the insult of bills with small numbers. It is safe to say that growing up, everything I learned about honesty, I learned from the family’s TV set, which was stolen.

There was no one at home to ruminate upon Karlo’s early retirement with me, though my family probably would have had little to offer but confused laughter. Even under the scrutiny of nonstop news coverage, Karlo’s dignity was incomprehensibly decent. It was too simple to decipher. News anchors would sigh in exasperation trying to explain an act that needed no explanation. I could not understand either. I could only emulate.

I was a gorilla pantomiming Karlo’s virtue, yet Karlo’s example was why I refused to cheat on school exams and Karlo’s example was why I bought my gun . . . in case I ever chanced upon an opportunity to underline dignity with blood. This is the very same gun that has received so much attention in the media of late.

The police must have told you—though I know it makes little difference—that the gun is broken. It would not fire when I bought it fourteen years ago and it would not fire when I held it to Robert Sampson’s terrified—yet somehow still smug—face last week.

Surely, you know that I never intended to use the weapon. After fourteen years sitting in my pocket as my house keys’ constant companion, the gun had become just another key to a door leading nowhere except to my childhood memories. Despite media speculation to the contrary, the chance to meet Karlo was the only reason for my enthusiasm in taking the job as Volunteer Player Transporter. But I admit this enthusiasm was blunted and twisted when you insisted upon driving Karlo to his matches—all of his matches—yourself.

And so that fateful day I found myself behind my car’s steering wheel, surrounded on all sides by heavy traffic and nonstop chatter. Robert Sampson, Karlo’s third-round adversary, would not shut up. He was warming up on me. He was hitting words at me like tennis balls at a brick wall. But I bruise easily.

“I’m gonna ram that old bastard’s serve right back to him,” Sampson kept saying, promising to turn Karlo’s most potent tool against him. Despite my unwavering belief in Karlo, the certainty of this cocky prodigy from Florida punctured my cool. Because it was true that Karlo had come to over-rely on his serve to end matches before his legs would tire, and it was true that Sampson had one of the best returns of serve in the game before that day.

(His doctors assure me that he will still have a long and lucrative career giving tennis lessons. I believe it will be a satisfying one, too. Under the pretense of “giving instruction,” Sampson will have the perfect excuse to exercise his favorite mouth muscles into Olympic form.)

While Robert Sampson babbled on in my backseat, I turned the radio up. I rolled the window down. Though cold rain splashed on my face, I could not awaken from a nightmarish doubt that Sampson would win the match, cutting short Karlo’s miraculous return to the world of tennis. I grew sad and tired and I rested my head on the steering wheel. It was then that I noticed the gun-shaped bulge in my pocket, as if for the first time.

You must believe me that when I pulled out the pistol (the broken pistol, I remind you) and pointed it at Robert Sampson’s chubby face, all I wanted was to finish the car ride in silence. Yes, I admit it was satisfying to see his mouth twist in terror, though in hindsight, his expression could have just been preparation to return a hard serve.

We will never know if Robert Sampson would have bested Karlo, but I saw his reflexes firsthand and they were electric. It would have been a close match.

“Shut up,” I began, but in a flash, Sampson had snatched the gun from my grasp and cracked its butt against my skull. He grabbed the door handle and launched himself out of the car.

How could I have known Sampson would react like that? How could Sampson have known that traffic had begun moving again? How could Sanford Ignatius, proud owner of a turbo-charged Mercedes Benz, have expected a world class tennis player to throw himself in front of his speeding car?

The crash left us in strange, different, terrible places. It delivered me to this jail cell and it sent Robert Sampson to the emergency room. I imagine it propelled Sanford Ignatius back to the Mercedes dealership. But worst of all, it returned Karlo Kassandri to retirement.

Mr. Stevenson, it was only natural that Karlo assumed the dark currents swirling in the tennis cosmos had once again conspired to fix a match, this time in his favor. But you know as well as I that the outcome mattered little to Karlo, only the perceived injustice. How could Karlo have done anything but withdraw from the ESTC in a volcanic torrent of insinuations?

You must forgive his allusions that your tournament is rigged, Mr. Stevenson. You know how Karlo is. He is passionate. He gets carried away. The things he said were borne of ignorance—he does not know that Sampson’s injuries were the product of spontaneous circumstances, as you and I do. You must forgive him openly questioning your integrity.

I know Karlo’s allegations have frightened the sponsors and that the tournament’s future is uncertain. I understand why you feel a public retaliation of words is necessary to save face and business, but Karlo is not a “hot-headed rabble rouser who would rather break a contract than break a sweat” as you claimed in the newspapers. He is not “an old, bounced-out ball.”

You must stop your public relations campaign to malign Karlo’s good name. Please, sir, let the future find Karlo in the Hall of Fame. Let people remember the hope, dignity, and gunfire he brought us. Do it for the confused youngsters sitting at home alone, pondering Karlo’s actions and feeling the ground tremble. Though I may have grown dormant, I pray that the world will always shudder with personal earthquakes.

My lawyer, a well-intentioned, young man, tells me it is a mistake to send this letter. But he has not spoken with you, grasped your hand, and seen that you are more than just a man of business. Crime and criminals are my lawyer’s daily routine. He measures decency only by its distance. Close the gap, Mr. Stevenson.

As a small side note, I must remind you that I too have covered a lot of ground recently. I am enclosing receipts for the gasoline I bought while transporting players during the first two rounds of the tournament. Would you please send the reimbursement check to my attention at the County Prison, care of Officer John Brown? I may be here awhile and this income will cover my subscription to Tennis World, which will soon need renewal.

Thank you for your time.

Your brother in tennis,

Carlos Villa Real

Henry Presente’s creative juices have stained the pages of Harpur Palate, Pear Noir!, The MacGuffin, SmokeLong Quarterly, Jelly Bucket, Reed Magazine, flashquake, and Broken Pencil, among other publications. Occasionally, a Pushcart Prize nomination has sopped up some of the sauce.

Q&A

Q: What was your inspiration for this story?

A: With this story, I wanted to take a tennis ball, inject it with decency and corruption and good intentions, throw it in the air, serve, and see whether it landed in or out.

Q. Besides Prime Number, what are some of your favorite literary magazines?

A: I’m a big fan of Harpur Palate and SmokeLong Quarterly.

Q: What’s your writing process?

A: I start with a rough grain of sand—be it a character, a concept, or a scenario—and then I add to it and sand it down a few thousand times until there’s something smooth and polished rolling around the computer screen.

Q: What living writer to you admire most and why?

A: I like Alex Shakar for how hard he tries and how he sometimes succeeds. And I like the homeless writers in Washington, DC who sell $1 newspapers filled with their words for the same reasons.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: Balance in life and being a good person. But if you’re talking about writing, then we’re talking about a new short story. Something light-hearted but intense.

The Claim Narratives by Stephen Ornes

Followed by Q&A

Stefan's job was to estimate when the end would come, and to whom it would most likely come, and what it would cost, in a variety of situations. He created statistical models, and populated those models with numbers, and ran those models, but really, the whole endeavor came down to money. He calculated monetary values for risks: Workplace injuries; surgical mishaps; automobile malfunctions and crashes; trees falling on houses; dismemberment due to farm equipment. Other actuaries consulted with him on matters of inland marine business. And other matters. Stefan was something of a prodigy in that world. Risk was his thing.

From the beginning, he'd thought of Tina as a calculated risk. They met online. She described herself as “adventurous” and “divorced.” He described himself as “ready to settle” and “perpetually restless.” Like the kid in The Giving Tree, he wrote in an email. He spent 15 years working like a hurricane, and he’d recently been promoted to an executive position at his reinsurance company. After describing himself in an email as “working like a hurricane,” he promptly followed up by explaining to her, in another email, that he was a casualty actuary who calculated risk, and he knew a thing or two about how much work a hurricane did, and how much money that work was worth. In his first draft of that email, he explained the relative merits of fitting a lognormal distribution to losses, and when a gamma or Pareto distribution makes more sense, and why his paper on mixing distributions had become something of a seminal reference in the field, but before he sent the email he deleted those details.

In a third email, he told her again that he worked for a reinsurance company.

“I like that you chose words that go against each other in your profile,” Tina said when she and Stefan met for the first time at a diner. They drank coffee and ordered the same kind of omelet, a western omelet, which at that diner meant they poured Pace picante sauce over some scrambled eggs.

“You’re ‘adventurous,’” he said because he didn’t know what else to say.

“I’d never read The Giving Tree,” she said as she tapped one long fingernail on the rim of a mug that said Peggy’s, “but then I bought a copy and I cried. Oh, I cried! I’ve been married before. No kids, but I wanted kids. I used to party. Not anymore.”

“Me neither,” Stefan said. She held up her coffee cup, and he held up his, and they toasted to not partying anymore. He felt regret even in that toast, but he suspected she did, too. She seemed like the kind of woman who was reluctant to grow up.

One night, after two gin and tonics, he told Tina that he’d gone to rehab for six months to kick a cocaine addiction. He told her that he felt like a widower, like cocaine was his dead spouse and he was grieving, always grieving. He’d finished rehab three years earlier and didn’t think it would be a problem anymore, but he thought she should know. Low risk of resuming addictive habit. (He said nothing about how he estimated the Value at Risk before starting rehab, and how close his calculations had been to the actual financial maximum loss, though that loss was dwarfed by the projected maximum loss of maintaining an expensive habit into middle age.)

“I get it,” Tina said. She had large eyes and golden skin and worked for a marketing firm. She dressed nicely. Stefan smiled because he thought she really did get it.

Another night, he told her that he’d already bought a four-bedroom house on a half-acre lot in Darien. He was renting it to a nice family—a dog, two kids with tutors—until he had his own family. She responded by saying she appreciated his earnestness and his candor, but she probably wouldn’t ever settle with him. He sold the house in Darien.

One night, at a restaurant, she asked him what reinsurance was.

“Insurance companies need insurance,” he said, “to cover their exposure.”

She burst out laughing. “You've already lost me but it sounds hilarious,” she said. “Cover their exposure!” Stefan didn't know what was so hilarious but he laughed, too.

She texted him from the bathroom. “Cvrin my xpozr rofl!” She attached a photo of a toilet paper roll and of her cleavage, taken in the bathroom mirror.

Tina introduced him to sexting. She showed him how to use letters and symbols to fashion vulgar pictures. They took videos of each other, and later of themselves. After they’d been together for two years, she spliced their camera-shot movies, and they watched them together and laughed and then stopped laughing when they got hot and bothered.

Stefan persisted with the talk about getting married and all that. Their disagreements were few and quickly resolved, often in bed. Before Tina, sex had been recreational and occasional and necessary, more like a Windows update or a new insurance model. It had been a variable, decidedly nonparametric, that was influential enough to drive him to meet people. Something interesting, but passing. Sex with Tina made sex seem more like an investment, an accumulation of carnal knowledge with both short-term dividends and the potential to lead to something larger in the future. Returns that, if one turned sex into a parametric variable, could be modeled, analyzed, and used for projections. He told her something like that, once.

She had pushed him off. “Shut the fuck off, actuarial nerd!” she cried. He fell back, surprised. For a moment, she looked horrified. Then her face broke into a smile and she pulled him toward her again. “I’m just kidding, Stefan. It’s hot. Really. I’m glad my tits remind you of work.”

He laughed. “Shut the fuck off?”

“Shut the fuck off,” she said, pushed him onto his back, and climbed on top.

Tina said she liked his dependability, and that he was predictable but still liked to have fun. He rented a yacht and on a moonless, overcast night he asked her to marry him. She couldn’t see the ring, but she gauged its heft with the cushion of her index finger. She bit her bottom lip, got caught up in the moment and said yes, yes, yes, Stefan. Yes, let’s marry.

The next day, she didn’t send a sexy text; she wrote: Baking a casserole! Hungry?

He texted back: Home after work, dear.

They thought it hilarious, this new kind of role-playing, like the day before they'd been feral, and now here they were, domesticated.

She convinced him to live in Greenwich, because she still had to go to the city sometimes and he still worked in Stamford, the reinsurance capital of the world. The nickname of that city was: “The City that Works.” Artless, accurate. A year after the wedding, she became pregnant; two years after the wedding, they had a three-month-old girl named Addie with her mother’s eyes and her father’s big head. Stefan doted, so much so that he surprised himself. Early on, he tried to build a spreadsheet that would help him quantify his affection for the child—he tried to identify his affection on a scale from 1-10, a measurement used in the same equation as what he called his “exhaustion quotient”—but eventually gave up. Tina quit her job in the city. Originally, she’d planned to go back to work but later said going back to work seemed awful.

One day she texted: Lasagna for dinner! Firing the cleaning lady! You? Neither thing was true.

Him: Humming. What else is new?

Her: Running errands, getting gas. Howz work?

He texted back: Rough day at the office.

She texted back: Bring the boss home to dinner! Kay?

And him: But I am the boss!

Her: No lipstick on your collar this time! I’ll kill her! Got it?

Things worsened about the time of Addie’s first birthday. Tina cried a lot at night, after Addie was asleep. Tina said she wondered if she was spending too much time with Addie, spoiling the child, rotting herself, though that hardly seemed possible. She couldn’t imagine going back to work, going back to the city, but maybe she needed a new job. She told Stefan she wanted to do something else. Maybe she wanted to be a nurse. Stefan tried to be supportive, but he felt the ground shift, and he made every effort to hold Addie as often as possible when he was home, to protect her from the tremors he was starting to feel, all the while his head spinning through equations that might help him minimize the ongoing losses, might help minimize the probable maximum. Tina saw therapists, enrolled and then dropped out of programs, found another marketing job. He scrambled to build models that might predict all the different ways the situation might lead, and what the outcomes and losses would be in each situation, and the probability of each situation.

“It’s like everyone pretends to be real,” she told Stefan, in tears, the night she quit for good, “But they’re not. They don’t know what matters. God, was I like that? Did I know what matters?”

“Of course you did,” Stefan said, “You still do.” He wasn’t sure what they were talking about.

“But do I? Do I?” she cried, holding him tighter. “How do you know if you know what matters? You're a . . . a human calculator! Why don’t I even know myself? How can I be a mother? How do you know? This isn't an equation! No matter where I know, people pretend to know what matters and no one does, but everyone rolls on anyway, every day.”

The texts didn’t change—they were still light, still make-believe—though he could detect changes in the tone and color.

Baby needs new shoes.

Hot enough for ya? LOL Turning to ash

Bring home the bacon fry it up in a pan.

One day in mid-November, when Addie was 18 months old, Stefan woke up and felt cold beneath his skin. The house was heated; that wasn’t the problem. Connecticut had entered November: that time of year when the world is wrapped in a dreary and damp blanket. At the beach visible from their bedroom window, cruel winds tumbled over the dark and turbulent waters of the sound and pounded the shore. Clouds washed the world in monochrome.

“It's like a slow suffocation,” was the first thing Tina said to him in the morning. She'd been looking out the window at the clouds. She had bags under her eyes, which were red, and he wondered how sleeplessness would affect projected losses.

He and Tina fought that morning, and he wasn’t sure what they were fighting about. She felt lost and trapped even though they had all the freedom and money they could want. He tried to empathize, but he didn’t really understand; he knew his limitations were painfully visible. They didn’t resolve anything; Tina slammed the door to Addie’s room. Stefan had a nine o’clock meeting and didn’t want to be late, so he calmly left the house and drove to work and had his meeting. Honestly, he didn't know why she was flailing, or how to help her. All he could do was estimate.

After his meeting, he closed the door to his office. The corner office had come with his promotion to a vice-president position. His coworkers said it was perfect for him. Out one side, the windows overlooked a string of large yachts moored to a long dock. Farther out in the sound, small islands appeared like a string of stone turtles. The other windows overlooked a small, old graveyard. The two views were separated by a 90-degree swivel in an expensive chair.

“Wealth!” said a coworker, jabbing his thumb toward the bobbing yachts.

“Or Death!” laughed another, pointing to the rotting teeth in the graveyard.

That day in mid-November, though, he closed his eyes and didn’t look out either window. The thing about risk, he reminded himself, is that it’s theoretical—until the moment something happens. A driver is fine until he crashes; a beachfront mansion stands tall until it’s leveled by a hurricane. Until a diagnosis, the risk of cancer is just a number that means nothing. Stefan believed every risk sat on the abstract possibility of a real incident. And that day felt like that kind of moment. The morning’s fight hadn’t been particularly eventful, but something about it seemed final.

He tried to ignore the uncertainty of it all. He hated uncertainty.

He texted: Big plans for the morning?

He set down the phone and stared at it. Thirty seconds later, which seemed like a long time, it buzzed with a return message.

Pedicure and bon-bons. As always.

Then: You know Addie loves Oprah.

He smiled. Maybe he’d been wrong. He turned to his work.

Then: I'll try not to leave the car running in the garage. JK!

Outside, empty and brittle trees drooped with despondence, the cold settled in and the gray sky looked like a heart attack. In his business, this time of year was known as renewal season. Actuaries reassessed existing contracts to ensure their reinsurance prices were both competitive and profitable. Actuaries scoured data and used software to simulate catastrophic events. Actuaries calculated expected values for payouts by multiplying the likelihood of an event by its expense.

Actuaries analyzed the past to quantify the future. And made lots of money.

Usually, he delegated contract renewals to lesser actuaries. But the company was doing so well that renewals had backed up, and so he set out to price one himself. He pulled a binder from a stack of binders—he preferred looking at the hard copies rather than the numbers on his dead, glowing screen—and began to read. The company applying for reinsurance was a small, Southern insurance company that insured nonprofit organizations. Stefan began absent-mindedly flipping through the pages.

Somewhere out in the office, an underwriter was on fire.

“At the end of the day,” the man barked, loud enough that everyone could hear, even Stefan in his closed office, “what matters is who's pitching and who's catching, and I'm asking you, who's pitching? Can ya tell me that, Brad? Cause I'm ready to send one out of the park. We gotta know who’s on board. This ship is sailing, Brad, and it sounds like you might miss it.”

Stefan shook his head and returned to the file. He'd never liked underwriters. He stopped flipping through the binder and landed on the Claim Narratives. Normally, he didn’t pay attention to them. Claim narratives were one- or two-sentence descriptions of tragedy; these described the claims that had been paid by the insured businesses—and, if the monetary amounts were high enough, the amount that the reinsurance company had paid.

Each line represented a very real event, a collapsing of risk into incident. Something happened, then someone had filed a claim, then the insurance company had paid money. Stefan began to read.

The first one: Goodwill warehouse. Forklift accident. Blindness.

Further down the page: Door opened on Big Brothers Big Sisters van while occupied. Passenger ejected.

And: Claimant struck by Boy Scouts of America ElderShuttle. Quadriplegic.

And: Ramp collapse. Loss of three digits. Skull contusion.

Stefan caught his breath. He began to imagine these scenes. Invariably, in his imagination, they happened on sunny days in quaint small towns where everyone spoke with a drawl. He'd never spent much time in the states covered by this company: Tennessee, Alabama, Louisiana, Georgia, part of South Carolina. Stefan had grown up in Sacramento but went to the East Coast for college and never returned. He’d never known the South. But here were its daily tragedies.

Deceased had heart attack in disabled HomeAssist elevator

Collapsed exhibit, children’s museum. Broken arm, concussion.

He read, and read, and read. He tried to crunch some numbers. He couldn’t think straight.

He texted: Sup?

Tina texted: Park. Lib. Store for groceries.

He stared at the phone, waiting for more, but it was silent. The binder lay open. He closed it. He watched the clock on his computer monitor change from 3:00 to 3:01. Outside the sky was darkening. He called it a day.

As he left, the fight with Tina loomed large in his mind. He'd go home and talk to her. Sort it out. Figure out what had changed. Take Addie out for hot chocolate. He turned off the monitor, turned out the light, nodded to the underwriter next door as he walked by the door—the underwriter winked and pointed at him, then inexplicably raised a fist in the air three times—and walked to the elevators.

Traffic wasn't bad yet. Stefan raced up I-95 with the fading sun on his left. It took him only about 15 minutes to get home with no traffic. He pulled into the garage at 3:30 and parked next to Tina's car.

“Tina?” he called as he walked in, though he knew by the heavy quietness that she was out. “Addie?”

He took his phone from his pocket and called her number, but she didn't answer, and he didn't leave a message. He wandered absent-mindedly from room to room, staring only at his phone. Waiting for her to call back. She didn’t. The playroom: Spotless. The bedrooms: Beds made, but definitely uninhabited. The kitchen: Tidy.

Something seemed so wrong about all of this. Tina was not neat; Tina was not tidy. They only ever picked up the mess at night. But now, every room looked unchanged from when they’d gone to bed last night. It was clean last night because the cleaning lady had been there yesterday afternoon.

Stefan sat down on his bed and loosened his tie. He closed his eyes. Tina's car was still in the garage. Not running, and empty. They were probably out for a walk. Park. Library. Groceries.

He stood up and was headed for the kitchen when he peeked into the den and noticed that the laptop was open, though the screen was dark. He'd come home to fix his family, but since they weren't there, nothing would be fixed. He texted Tina.

Busy day at the office?

She texted back, almost immediately: The usual. Trying not to burn things.

He tried to call again, but she didn't answer. There was nothing to do but work, he supposed. He pushed a button on the laptop and the screen bristled as it came to life.

A browser window, open to an unfamiliar web page. An email provider Stefan had never heard of. An email address. An email, on the screen.

Hi Debbie, Sure, it's fine to come earlier. Sorry to have upset you. But no need to panic! We can take her at 9:00 or later, no problem. Let me know if there's any foods she's allergic to for lunch. Mary

Stefan scrolled down.

Mary, I don't think it's going to work, then. I don't know what to do. My first interview is at 10:00 so I really need to drop off my sweet sweet daughter by 9:30 at the latest to get there on time. I just don't know what to do but thanks for your offer. Any way 9:30 or even 9:15 will work? You are an angel you are blessed. God bless you for helping people like me. Debbie.

Stefan recognized that phrase: “You are an angel you are blessed” because Tina often whispered it to Addie at night, the last thing the little girl heard before falling asleep. Stefan told himself to close the window but read the rest of the email chain instead.

Dear Debbie, You and your sweet daughter can stop worrying for today, anyway! Bob and I will be home all day. My kids are grown and away, and I miss having a toddler in the house. We'll be up and at 'em by 10. We live at 3510 Rider Place in Darien – it's a gray, two-story house on the corner. We'll be watching for you! Blessings on you Debbie, and good luck in your interview! Mary

Mary, I feel like the luckiest mom in Connecticut. Finally I have an interview for a job, and I don't have to cancel because of my sweet Angel daughter. You were sent to me by God. I know it! And I know that my late husband is smiling down on me from heaven, and smiling down on you, too, and things are going to change for me and for Addie. I just know it. Love, Debbie

The last email read:

Dear Debbie, My husband showed me your notice on Craig's List. We are so sorry for your loss, so very sorry, and I know what it's like to be scraping by. Trust me! I was a single mom to three wonderful kids, but it was tough. They grew up. I met Bob, a wonderful man. I'm not scraping by now, and I want to tell you that things can change. Don't despair. I can watch your daughter today. I'm available and home, and I can assure you that our house is safe and we will take the best care of her. I'm sure you've received a dozen other offers, but if you still need someone, please email me back. Love, Mary Pelham

Stefan sat down. He clicked on the inbox and found other messages from other people, all sent the night before, all offering “Debbie” to take care of her dear daughter. He closed his eyes, then he opened them again. His heart raced; Addie was at the home of Mary and Bob. Or was she?

He texted Tina: 's news?

Tina: Boring day. No new tale to tell!

Him: Early dinner?

Tina: No way! The house is a mess. Maybe take out.

Stefan felt sick. He called; Tina didn't answer. He looked again through the inbox and found, the week before, and the week before that, other, similar messages. From well-wishers. They offered help to “Susan” or “Vicky” or “Sarah.” Addie had been spending many days in the homes of strangers.

Then he found email messages from someone else. Doug. One from Tina to Doug, from the night before.

Big D, and I know you know what I mean by Big, Still on for Six Flags! Pick us up at 9 – A goes to Darien, on the way. Back by 4, okay? Can't wait - Xoxo, Teen

Stefan looked out the window; snow had begun to fall.

He wrote down the address and ran to his car. He felt sick. He drove to Darien. It was 3:30.

Mary Pelham was a heavy woman with a worn face, mid-60s, standing behind a screen door and pinching her bottom lip. Her other hand was on her hip.

“My daughter's here,” Stefan said. “Addie. You have my daughter.”

Mary's eyes widened, and she put both hands on her hips.

“I'm sorry,” she said, nodding. “I think you have the wrong house.”

“Mary Pelham, 3510 Rider Place, Darien. You have my daughter. Don't you? Please.”

“Please leave, sir. You're making me quite uncomfortable.”

“My wife's name is Tina but she told you her name was Debbie. She said I was dead, which isn't true, and I think she's with someone named Doug. Addie is my daughter and I want to take her home.”

She strained to look past him, over his shoulder, at his car. He looked at his silent phone. It was 4:00; the sun was falling; a street light flickered on behind him. The light dusting of snow had left everything dreamy and white.

“Addie!” he called into the house.

“No!” Mary said, shuffling to stand in front of him. “I don't know who you are, or who Addie is, but I will call the police.”

“Yes,” he said. “Let's call the police. You will be charged with kidnapping. Addie is the little girl you were taking care of today.”

“No,” she said. “Please go away.”

“Daddy!” cried Addie, running up behind Mary Pelham. She had two braids in her blond hair, one on each side. “Surprise! Ha ha ha! Where's mommy? I am an Angel.”

Stefan tried to smile, then he looked at Mary and yanked on the screen door. It had been locked, but he pulled so hard it broke. A piece of the metal latch landed on the concrete step. Stefan picked it up and handed it to Mary.

He was about to speak when Addie jumped into his arms. She had dark circles under her eyes; she went limp in his arms. Stefan glared at Mary, then carried his daughter to the car and installed her in her seat in the back, facing forward. He started the car, turned on the heat, and told her they would leave soon. By the time he turned around, she was asleep. He stepped out of the car again.

“She didn't nap,” Mary said.

“When are the police going to be here?” Stefan asked.

“I didn't call,” Mary said. “But if you leave before the girl's mother gets here, I will. I've got your plates memorized.”

Stefan folded his arms and leaned against the car. Snow covered the lawn, but there were footprints running through the front yard. It wasn't a bad street. Mary didn't come across as a bad person. Addie had probably been safe. More lights popped on overhead; they were bright, making each passing car look like it came from a showroom. Stefan got out his phone.

Where r u? He typed.

Out there, in the dark somewhere, her fingertips dancing lightly across the lighted keys.

She texted back: Home. Making dinner.

Something harsh and tight moved across Stefan's face.

He glanced at the car where Addie was sleeping. Please don't be like us, he thought.

He texted: How's our girl?

Tina: Sound asleep. Long nap.

What's for dinner? He typed, but held his finger over “send” without pushing.

“I think that's her,” Mary said. “She had a ride to her interview.”

Stefan looked up.

“I don't think there was an interview,” he said.

A white sedan approached. It slowed as it neared. It passed under the nearest streetlight, and Stefan saw a flurry of hands in the front seat. Tina's hands. A reflection caught her face. She sat in the passenger seat; a man with a short beard drove. Stefan had never seen the man before. The driver looked confused; Tina put her hand over her mouth and stared down at her lap, right where the phone must be sitting. Time seemed to slow. She looked up again.

Their eyes met, and without looking down Stefan pushed “send.” He held her eyes as the car passed directly in front of the driveway. Her face was blank, but then her eyes quickly shifted down. The message had arrived on her phone. It probably made that annoying sound of a passing jetliner. She looked up again; she held her bottom lip between her teeth. Then she was looking backward as they passed. Then she and her companion Doug were gone, the sedan was gone, and then it turned a corner, and Stefan and Addie were alone in the driveway and it was just as quiet as it had been before. Maybe more quiet.

He thought his body would snap in a million places. In all his figuring, all the models, this variable had never appeared, never been valued, never had a probability attached to it. His face felt cold within and without. This was his hurricane; his accident; his blindness; his paralysis; his forklift. This was the promise of risk, fulfilled; this was a claim. This was an act of God.

Stefan's phone vibrated.

Lasagna. See you soon?

I'll be home late. He texted. Don't wait up. He didn't know why he wrote back. After a hurricane, people don't come out of their houses and talk about the weather. He knew that the smart way to see a catastrophe was to look forward, press on, begin the reconstruction, but for a few more seconds he appreciated having a last tether to what had already been lost.

Mary sighed. Stefan had forgotten she was there. He looked at her, saw her breath escape her mouth and envelop her like a wall. She'd come out of the house and was wearing a coat over her knee-length dress, and clogs.

“I guess I'm a fool, after all,” she said, slapping her hand on her thighs and walking away, into the house. “No cops,” she called over her shoulder.

“Wait,” Stefan said. “Wait. What do I owe you?”

Mary turned around and shook her head. “You don't.”

“For taking care... For the door. I should pay you some money.”

“Please don't,” Mary said.

“For taking care of Addie.”

“No, don't.”

But that's how we know this happened, he thought. That's how we know.

Mary walked into the house, and the broken door slammed behind her, then bounced, then shut again, then bounced less, then shut quieter, then finally was still, half-open. Stefan, alone in the snow in the yard, slowly closed his wallet and returned to the car, where his daughter was sleeping. He leaned into the backseat and cupped her cheek in his hand. It was warm and soft, and she smiled in her sleep.

Stephen Ornes writes from a converted shed in his backyard in Nashville, Tenn. His work has also appeared in One Story, Arcadia, Vestal Review, the New Haven Review, and elsewhere. Visit him online at stephenornes.com.

Q&A

Q: What was your inspiration for this story?

A: I worked for a short while at a reinsurance company in Stamford, Connecticut, and I drew details from that experience for this story. Unlike Stefan, the prodigious actuary and protagonist of my story, I was not particularly well-suited for the actuarial life. The idea for the plot came from events that unfolded while I was living in Connecticut: A mother posted fabricated stories of tragedy and loss on Craig's List, soliciting strangers to watch her children while she claimed to be looking for a job. I wondered: Where could that lead?

Q: Besides Prime Number, what are some of your favorite literary magazines?

A: One Story, PANK, Glimmer Train.

Q: What’s your writing process?

A: I have three children and a full-time writing job, so writing fiction is done furtively and desperately, in small pieces, during time in-between other commitments.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: I'm shopping around a science-fiction novel about the scientist who finds a pocket of dark matter embedded in the Earth's crust. I'm also working on a novel about an 18th century mathematician.

This Hallowed Ground by Michael K. Bourdaghs

Followed by Q&A

Mischa encountered a samurai on his second day in Tokyo. When he stepped off the local commuter train at Tama that morning, none of the other disembarking passengers paid any heed to the life-sized wooden cutout propped up in a corner of the station. As everyone else walked straight for the exit, Mischa paused in front of the crudely drawn figure. One of the samurai’s stubby hands pawed the hilt of his sword, while the other hid behind his back—a pose that relieved the amateur artist of any need to paint it. Mischa adopted an identical posture in his own rather portly body. The plywood warrior delighted Mischa; everything about Japan delighted him.

A random thought popped into his mind: how short people were in the old days! The samurai’s top knot barely reached Mischa’s chin. A second random thought: the black-and-white memory of a 1959 vacation snapshot, nine-year-old Mischa poking his face through a hole in a cutout of Mount Rushmore to pose as Lincoln. His father, still wearing his seed corn cap, took the place of Jefferson; his mother had snapped the photo.

Fifty years later Mischa found himself playing tourist again. But it was a graying Mischa who had traveled to Japan—a Mischa with a divorce and two heart operations to his curriculum vitae, a Mischa who had devoted the previous year to nursing his father across the terminal stages of a vicious compound of Alzheimer’s and melanoma. He had arrived at Tama Station on this cold March morning to inspect the flat that in two days would become his home for the year. He carried in his pocket a small map with instructions on how to get from his hotel in Musashi-sakai to the apartment, two stops away on the Seibu-Tamagawa line.

Mischa bid sayonara to the wooden samurai. Outside the station gate he was delighted to discover a small open-air market, with a fruit stand, a vegetable shop, and a fish monger. Hewing to the handwritten map, he wended his way through a maze of narrow streets before locating the building. Fuchu Heights Terrace, the sign said in English. There was no elevator. He climbed an open-air staircase to the third floor, puffing with the effort, and unlocked the door to #302. A dim light greeted him: the beige curtains were all drawn shut against the morning sunlight. He remembered to remove his shoes in the entryway. In stocking-feet, he walked the length of the flat: it took nine seconds, roundtrip. A miniature dining table with two chairs in the front room, a twin bed, dresser, and metal desk in the back. Mischa could already glimpse comic stories he would tell back home in Iowa about the telephone-booth bathroom, about the door lintels that scraped his head. It was all delightful.

He locked up the apartment and retraced his route to the station. Waiting for the train, he again studied the wooden samurai, which he decided must have been a local classroom art project. The warrior’s name was emblazoned across his chest, three Chinese characters in thick black brushstrokes. Mischa had thrown himself into studying Japanese six months earlier, when the possibility of this visiting professor gig first arose. But of the thousands of characters used in the language, his aging brain had mastered only a few dozen. By a stroke of luck, one of these was the first character in the samurai’s name: Mischa knew it meant “nearby” or “close at hand.” He pulled out the small leatherbound notebook he kept in his jacket pocket and traced the three characters.

He needed to keep moving to hold off the jet lag. Instead of returning to his hotel, he took the Chuo Line train into the city center and visited Tokyo Tower. He walked from there to Zojoji Temple, where he admired the stately cedar planted in 1879 by Ulysses S. Grant. He hailed a taxi and showed the driver a scrap of paper on which the hotel desk clerk had written “Ochanomizu” in Japanese. According to his guidebook, Ochanomizu was full of music shops. Mischa needed to buy an electric cello; he’d left his acoustic Dunov back home. A new electric cello would allow him to practice through headphones without disturbing his neighbors here in Tokyo—an issue that never arose at his Iowa farmhouse.

Mischa had been playing cello since childhood. But this would be his first electric instrument.

***

The Japanese academic year began on April Fool’s Day: a delightful coincidence. At ten o’clock on the first morning of Mischa’s term as Visiting Professor at Musashino Women’s University, he sipped aromatic coffee in the office of Fujiwara-sensei, the man whose unexpected invitation had nudged into motion the chain of events that carried Mischa across the Pacific.

Fujiwara’s letter arrived with perspicuous timing. Mischa’s father had just entered the grim final spiral of his illness. Moreover, at Mayo College a posse of assistant professors had burst into open rebellion, demanding a revised curriculum that emphasized relevance and seemed to center on the lowest forms of culture: animated cartoons, gangsta rap, eating disorders. It was only Mischa’s second year at Mayo—he’d resigned tenure at Southwest Tennessee State to move back home to look after his father—and he hesitated to entangle himself in internecine disputes. But he was also a lover of good novels and poetry and almost involuntarily found himself enlisted into the conservative opposition, the aging full professors who took to calling themselves the “White Guard.”

Mischa felt wary among his own faction. His co-conspirators were all, like him, nearing retirement. Yet the others seemed more polished and urbane. They drank wine, not whiskey. Around them Mischa felt rumpled and sweaty, ever the awkward farmboy. They were genuine scholars, too; Mischa hadn’t published a serious piece in years, and he suspected they sneered at the book reviews of contemporary fiction he wrote for several Midwest newspapers. Moreover, for all their rallying around the battle flag of Literature, his colleagues seemed to have little use for living writers. When they drafted their counter-manifesto for the Board of Regents, insisting that Mayo adopt a Great Books curriculum, Mischa suggested four contemporary titles for the list. His proposal floated away unnoticed, a humble bit of cottonwood fluff in the summer breeze.

Fujiwara-sensei’s invitation arrived just as Mischa began to sense that, whatever the outcome of the curriculum wars, he would end up on the losing side. It was a wistful realization; his heart wasn’t in this battle. For more than a year, he’d spent every evening in the nursing home, trying to satisfy the dying widower’s incoherent demands. With his father’s end now mercifully in sight, Mischa had no stomach for faculty meetings spent bickering over graduation requirements. Mischa’s current desires were much simpler: he wanted to eat, drink, fuck, laugh, waltz, ice skate, play cello, smell strong coffee. He wanted to throw his arms out to hug the world and see if it might still hug him back. A year in Japan sounded, in a word, delightful.

And so on the morning of April Fool’s Day Mischa sat in Fujiwara’s office. Hardcovers and paperbacks lined the shelves in the room, each meticulously wrapped in a clear vinyl protector. They included titles Mischa remembered from his grad school days in Minneapolis: I.A. Richards, F.R. Leavis, William Empson. Fujiwara specialized in British Romantic poetry. But in his letter he praised Mischa’s scholarship—he had somehow dug up the old articles on Carl Sandburg, Stephen Crane, Walt Whitman.

Fujiwara seemed the most decent, cultured human on the planet. In a photograph hanging behind his desk, Fujiwara stood with several other men, all clad in somber black kimonos. That morning in his office he wore a tailored charcoal suit with a royal-blue silk necktie. His distinguished gray hair was combed impeccably, and he wore utterly unfashionable—and therefore somehow utterly elegant—steel-rimmed eyeglasses. Mischa admired the delicate touch with which Fujiwara measured out spoonfuls of coffee beans into a hand-cranked grinder. He brewed one cup at a time, gracefully decanting water from a tea kettle into the paper filter, letting it seep down into a glossy china cup that sat on a proper saucer.

“You will find our Japanese students quite shy and reluctant to speak or even to think,” he told Mischa. Fujiwara’s English preserved traces of the two years he’d spent at Oxford in the 1970s. “They are our lost generation, raised without any feel for literature. They grew up on video games and cell phones, with parents who read only comic books.”

“They sound like my students in Iowa,” Mischa said.

“No! It is much worse here. In America, you have standards.” Fujiwara’s eyes glinted, and Mischa understood there was no margin for joking here. “We even have professors at this institution who prefer to teach television commercials and comic books. You must help me hold the line. You must give our students real literature. That is why you are here.”

Mischa liked Fujiwara—the man radiated sheer decency. But this summons to battle was identical to the one that had sent Mischa fleeing Cedar Rapids, a deserter from the culture wars. Time to venture boldly forth and change the subject. Mischa pulled out his notebook and pointed to the three Chinese characters he copied down at the train station.

“Ah, yes. Kondo Isami. A great samurai from this area. In the 1860s, during the last years of the shogun, he led the Shinsengumi. It was a last-ditch effort to preserve the old order. I suppose they were what we today would call a death squad, roaming the streets of Kyoto, cutting down advocates of reform. In the end they were defeated, but they became legendary for their sincerity.”

Fujiwara-sensei picked up an old-fashioned Mont Blanc fountain pen from his desk. On the notepad, just above Mischa’s childish scrawl, he sketched in the correct forms for the three characters, his handwriting a work of art, with each figure resting in perfect equipoise. A small gesture of correction: with no fuss, Fujiwara had demonstrated the proper form, and Mischa knew that he should follow.

After coffee, Fujiwara guided Mischa to the campus personnel office to sign paperwork. In the corridor, another professor strode up to them and extended his hand.